003. ICONS

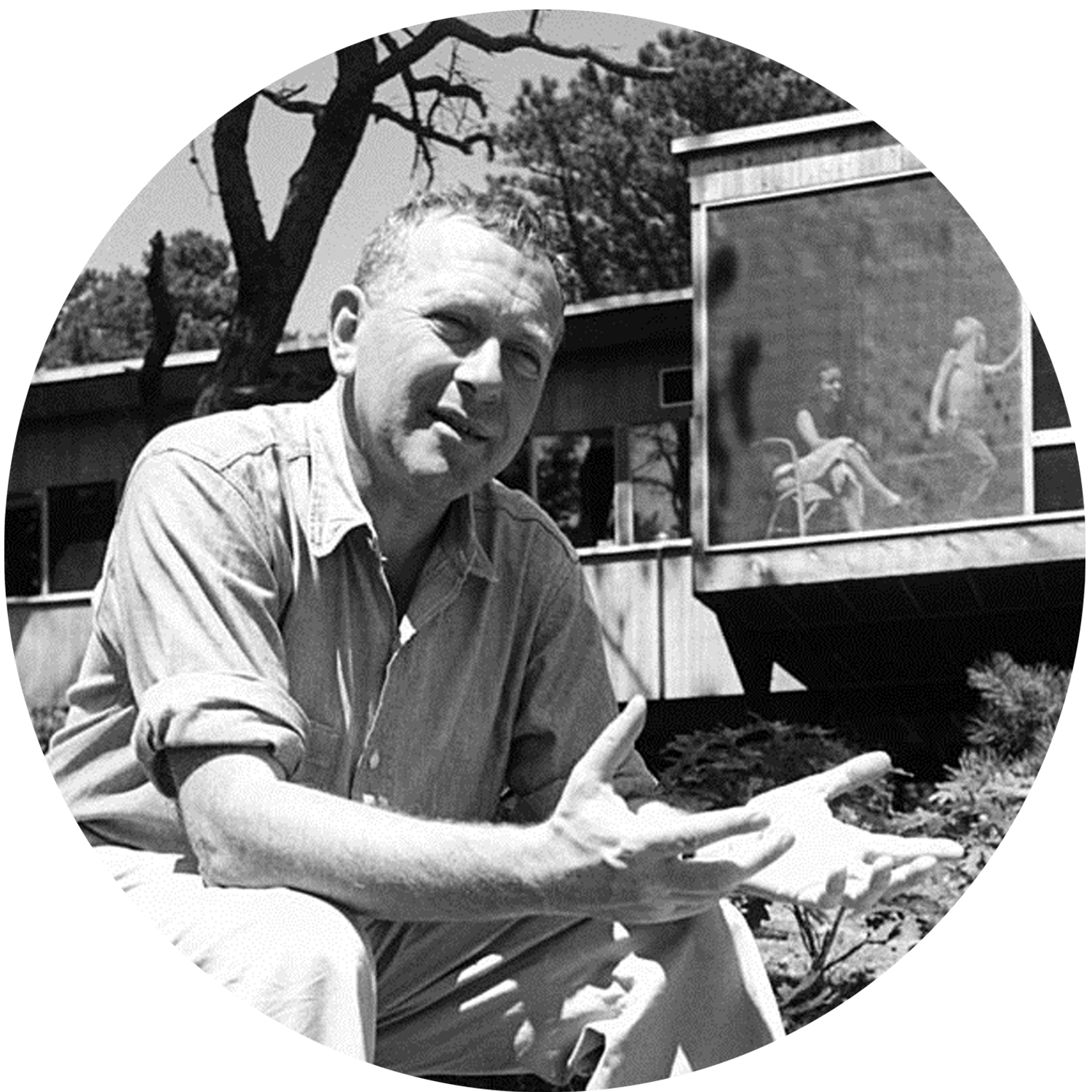

Marco zanuso

Written by Wava Carpenter

Italian designer Marco Zanuso (1916–2001) helped forge some of the most fundamental ideals and approaches to design practice in the modernist era—ideals and approaches that are still valued in the industry today, even as the definition of design has shifted and expanded. Starting in the 1940s, he developed a number of technical and methodological innovations that had a seismic impact on design history, including the first application of foam rubber in furniture upholstery and the first chair to be entirely fabricated from injection-molded plastic (the latter of which arose in the context of children’s furniture). Many of Zanuso’s greatest achievements involved the nuts and bolts of design practice, but one need not delve into the complicated details of industrial fabrication to grasp in his large body of work an uncanny flair for form. In piece after piece, Zanuso found balance between technological innovation and aesthetic desirability. Along the way, his furniture, appliances, lighting, and buildings acquired archetypal status, exemplifying how rational, democratic, and sensual design can be.

At an early age Zanuso began exhibiting a fascination with how things are made. The son of a doctor, he studied architecture and urban planning at the Politecnico di Milano, where he was introduced to and deeply influenced by the rationalist architects of the day, such as Giuseppe Terragni and Ernesto Rogers. Based in Italy in the 1930s, rationalism was a modernist movement predicated on the view that design should be directed toward the actualization of social aims. Its practitioners embraced new materials and technologies and eschewed extraneous ornamentation in order to place greater emphasis on function and affordability. Before World War II, rationalist design, like the Bauhaus and Le Corbusier works that influenced it, tended toward a severe and rigid aesthetic. In the hands of the next generation, modernism in Italy would find a softer, more organic expression. Zanuso’s work led the way toward this more lyrical iteration of modernism.

Zanuso graduated from university in 1939, just as Italy was entering World War II. After serving in the navy for four and a half years—an experience he later credited for his intense interest in new technologies—he returned home and opened his own design and architecture office in 1945. In the immediate aftermath of the war, Italian architects found limited opportunities to practice, so Zanuso joined the editorial team at Domus magazine under his mentor Ernesto Rogers. A few years later, Zanuso followed Rogers to Casabella magazine. In this early postwar period in Italy, under the shadow of devastation wrought by the war, the architecture community intensely debated whether design should focus on solving problems for the masses—mass-producing goods and housing as inexpensively as possible—or focus on the middle class, by merging industrial and artisanal methods while drawing from Italian traditions to bring art into everyday life. Rogers was a vocal advocate of the former paradigm, but Zanuso, while he favored highly rational methodologies, did not shy away from making things as beautiful and as “artful” as he could.

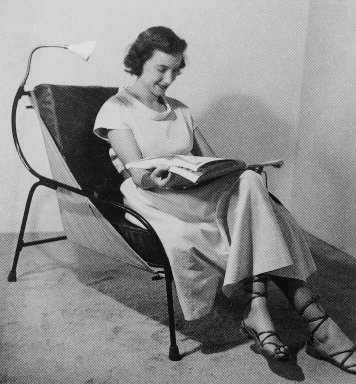

One of Zanuso’s earliest projects, and the one that put him on the international stage, was his entry to the Museum of Modern Art’s International Competition for Low-Cost Furniture in 1948. It featured a mechanical joining system of his own invention, in which a slim and sinewy tubular-steel frame supported a suspended fabric seating “cone,” accompanied by a built-in reading light and drink holder. Although he lost out to the likes of Charles Eames and Robin Day, Zanuso’s imaginative biomorphic lounge chair foreshadowed a lifelong drive to break new ground in construction techniques and material use.

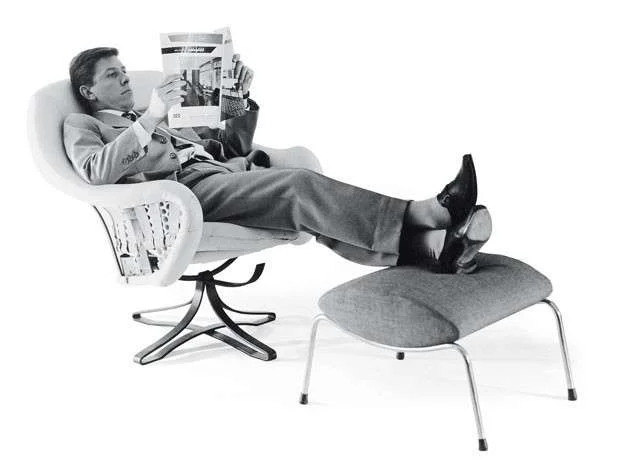

As a result of the acclaim Zanuso received from the MoMA exhibition, the Pirelli tire company approached him to explore innovative applications for their newly developed foam rubber material. His first idea was to use it in automobile seating, but he immediately began to envision its application in domestic furniture. “Numerous experiments made it apparent that the implications for the field of upholstered furniture were enormous,” Zanuso wrote in his 1983 essay “Design and Society.” The material would “revolutionize not only padding systems but also structural, manufacturing, and formal possibilities.” Zanuso helped to launch Arflex, one of the first companies in Italy dedicated to making furniture on an industrial scale. Soon after, at the 1951 Triennale di Milano, his still-produced Lady armchair won the Compasso d’Oro prize, the first of many accolades to come.

The holistic approach Zanuso took with Arflex—concerning himself with the details of a project from start to finish—became his standard mode of operation in his design work. He preferred to work like a project manager, not only conceiving a design on paper, but also orchestrating the most efficient manufacturing strategy, always with an eye toward producing in the thousands. Numerous companies were happy to work with him on his terms: Alessi, Alfa Romeo, Brionvega, C&B Italia, Elam, Gavina, Kartell, Lavazza, MiM, Necchi, Oluce, SIT Siemens, Techniform, Vortice Elettrosociali, Zanotta, and more. Large-scale firms such as Olivetti and IBM tapped him to design some of their industrial facilities as well.

Despite his insistence on retaining a great deal of control over his projects from beginning to end, he did not shy away from collaboration. And, no doubt, he had an eye for extraordinary talent. He regularly invited major artists, such as Lucio Fontana and Gianni Dova, to create artistic interventions on his private and public architectural facades and interiors. He relied on Renzo Piano as his teaching assistant at the Politecnico. He charged Cini Boeri with designing homey interiors for his architectural projects; among her most notable accomplishments is her sensitive work for Zanuso’s institutes for children, girls, and unwed mothers in the 1950s. He gave Aldo Rossi and Luca Meda their first jobs. And most famously, in 1957, he began a two-decade-long partnership with German designer Richard Sapper, with whom he shared credit for some of the most iconic works of Italian industrial design of the twentieth century.

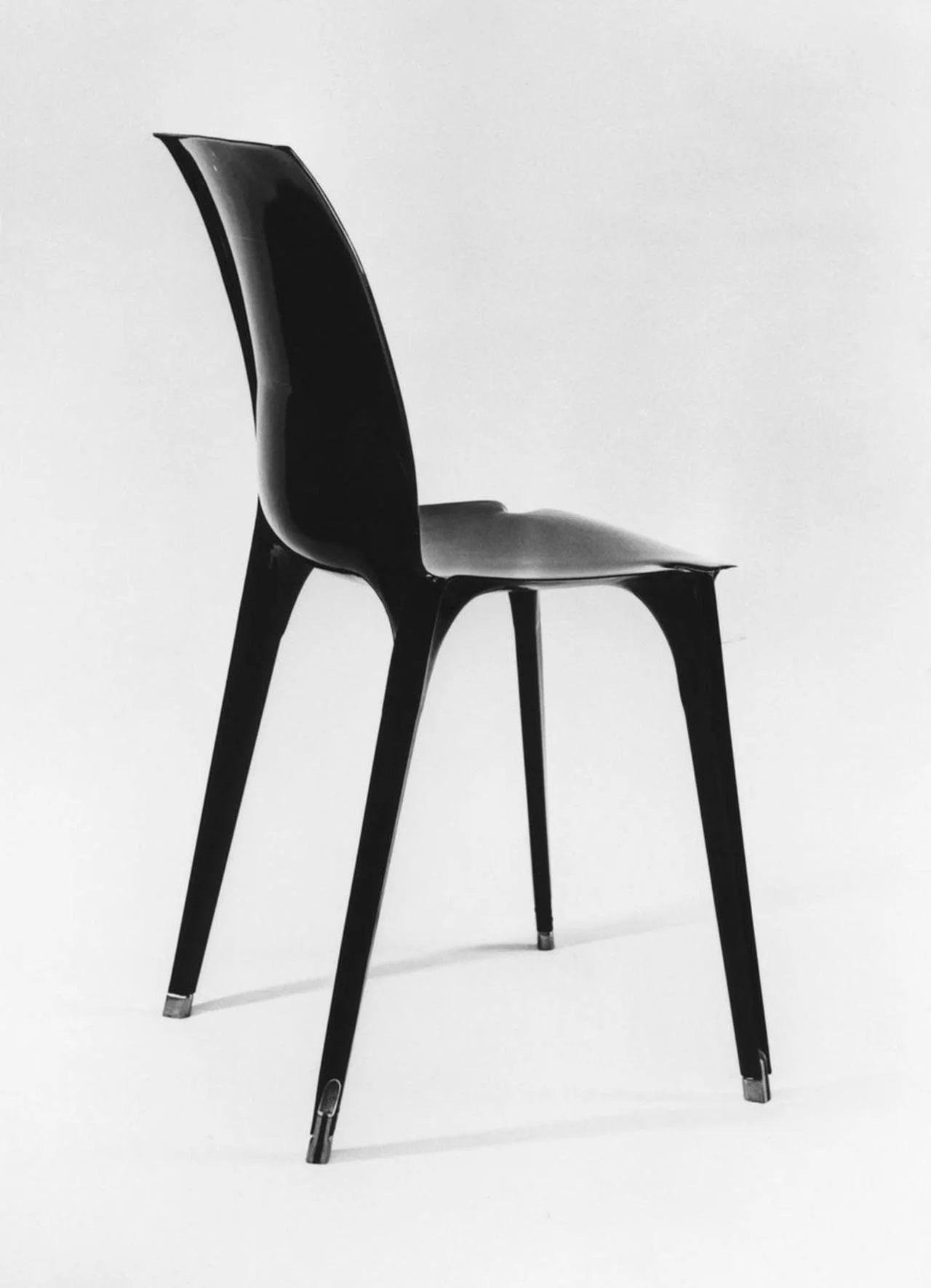

One such icon is the deceptively simple, sturdy, yet elegant Lambda chair. Before Gavina began producing it in 1964, Zanuso and Sapper had spent years exploring materials for chair design, and had settled on a hyper-streamlined automotive fabrication process in which sheet metal is stamped out, spot-welded, and spray enameled. The research behind the Lambda design led to another Zanuso and Sapper icon: the model K4999 child's chair (1960–64) for Kartell, which marked the first structural application of polyethylene plastic in furniture.

In recalling the path that led from the Lambda to the K4999, Zanuso wrote in “Design and Society”:

“In connection with a commission to design classroom furniture for the city of Milan, we had already been experimenting with a scaled-down stacking version of the Lambda for elementary schools. As we were looking for alternatives to sheet metal, a material inappropriate for this particular application, a notable drop in the price of polyethylene on the expiration of international patents opened up completely new possibilities. This new material, in turn, led to a rethinking of the formal and structural characteristics of the chair and, consequently, to much additional research. The final result, the Child’s Chair, surprised even us; because of the various stacking possibilities we had developed as a result of structural requirements imposed by the use of polyethylene, we had created a chair that was also a toy, which would stimulate a child’s fantasy in his construction of castles, towers, trains, and slides. At the same time, it was indestructible, and soft enough that it could not harm anyone, yet too heavy to be thrown.”

Today Zanuso is considered a monumental figure in the history of design, both in Italy and around the world. His way of working a design problem from innumerable angles, and the sheer determination with which he pursued optimal solutions to every challenge he encountered, is still instructive, particularly from the vantage point of today’s fast and furious world. Yet he was far from a cold intellect. Even as he rationalized production and materials, he always considered emotional, humane factors in his definition of function—from the way a radio fits in your kitchen (Brionvega TS-502, 1964) or a phone rests against your face (Grillo folding phone, 1966), to the way his own home was furnished with state-of-the-art modernist designs alongside antique family heirlooms. For Zanuso, the rational never precluded the human and personal. While implementing thoroughly planned systems on a vast scale, he never failed to take into consideration the small joys that make life worth living.