003. Icons

Ko Verzuu and the ADO Workshop

Written by Kimberlie Birks

As sculptural as they are playful, ADO toys possess all the qualities that child design enthusiasts appreciate: function, form, fantasy, and bold use of color. Add to these a beautiful patina from years of play and it quickly becomes evident why these postwar Dutch toys are coveted and collected. And yet, as their very name—an acronym for "Arbeid door Onvolwaardigen," or “Work by the Handicapped”—hints at, the story behind them brings an entirely new luster to each object, rendering it as striking in spirit as it is in form.

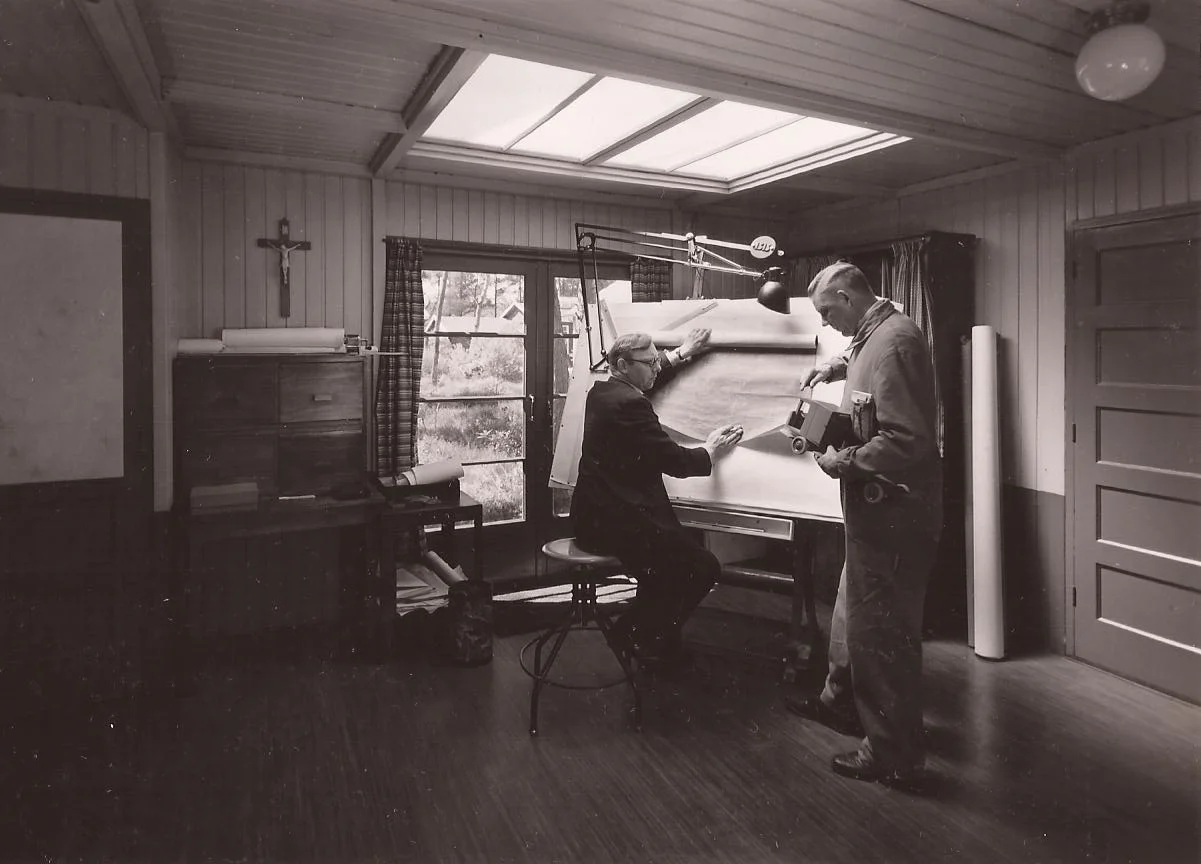

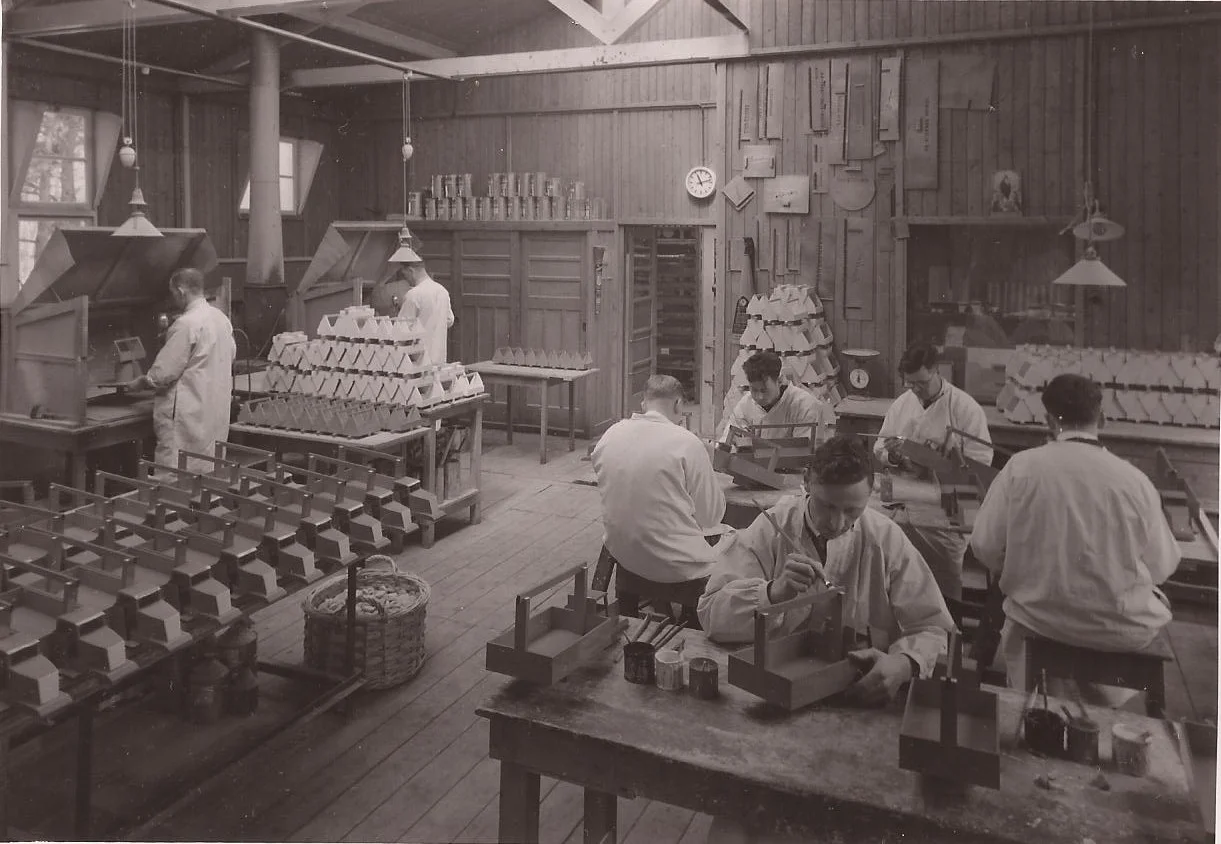

In 1925 Willem Bronkhorst, the medical director of the Dutch tuberculosis sanatorium Berg en Bosch, was seeking an overseer for his recently established physical therapy program. The ADO “work therapy” program was designed to provide patients in the final stages of recovery a woodworking studio where they could regain their strength through light physical activity. When Bronkhorst appointed Jacobus Johannes Josephus (Ko) Verzuu, a construction supervisor in the city of Utrecht and the son of a Dutch rail worker, to the role, it was an unlikely choice. Though it's unclear how they met, Bronkhorst and Verzuu immediately connected over their shared passion for art, which launched Verzuu into a thirty-year career supervising the construction of wooden toys. For Verzuu, the decision to focus on producing toys was an easy one: the work was easily segmented and demanded less physical exertion from the patients, and the machinery and storage needs were minimal. Often described as “full of enthusiasm, brimful of plans, and exhilarated by his work,” Verzuu’s dynamism, idealism, and creativity truly blossomed at the sanatorium.

Verzuu immersed himself in the artistic and educational ideas of the modernist avant-garde, often testing his designs on his eleven children. Branded with its now-characteristic trademark, each ADO toy became increasingly bold in design, with bright colors and abstract shapes reflecting Verzuu’s knowledge of the Bauhaus and de Stijl ideologies, along with the influence of Dutch architects and furniture designers Gerrit Rietveld and Henrik Wouda. This simplified visual vocabulary was underpinned by a nuanced argument on the artistic and educational merit of toys. “The shape should not be a miniature copy of the original, of which the young child’s mind does not understand the many details and which forms a dead end for the imagination,” Verzuu stated in a 1934–35 ADO toy vehicle catalog; “quite the reverse—the shape, with a lack of elaboration and well-chosen proportions should serve to show the essence of an object.” A firm believer in the power of aesthetic activity to shape everyday life, Verzuu was drawn to the work of educational theorist Maria Montessori, and became a prominent voice in burgeoning discussions on the ability of toys to educate a child in art appreciation. ADO toys were intended to feed children’s imaginations and inform them about the beauty of life.

During the three decades Verzuu served as the driving force behind ADO, the toys became a household presence in the Netherlands and Belgium. The Netherlands imported most of its toys from Germany, and was in need of “good toys, well designed, well made, and gaily colored.” The ADO workshop consisted of approximately forty worker-patients, and so, in 1932 when the Dutch department store de Bijenkorf requested that its windows be decorated with ADO toys, supply quickly sold out. By 1932, ADO was publishing its own catalog, which soon thereafter listed exports to Belgium, Britain, the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), and South Africa. By the time Verzuu left Berg en Bosch in 1955, ADO was supplying goods to 137 shops. But the spirit that Verzuu had brought to ADO shifted following his departure. The workshop left the sanatorium and changed the acronym’s meaning to "Apart, Doelmatig, Onverwoestbaar," or “Original, Functional, Indestructible,” and altered its design aesthetic. Furthermore, the advent of plastics in the 1960s brought great changes to the toy market, diminishing the demand for wooden toys.

Beloved for their modernist colors, proportions, and shapes, ADO toys have since become collector's items. As one of the first designers to focus on children’s toys, Verzuu should have a prominent place in the history of twentieth-century design. His inclusion in the Speelgoed ADO Toys exhibition at the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam in 1994 and in the 2012 landmark exhibition Century of the Child: Growing by Design at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City constitutes the first steps in the journey to rediscover this important name in design history. As one looks at the objects he designed, worn by time and love, one cannot help but see beyond their refined design to embrace a distinctly tactile approach to education. There is something incredibly poetic in the idea that tuberculosis patients slowly recovering from their brush with death crafted such hopeful, life-affirming objects. This history is only enhanced by the objects’ unlikely designer, Ko Verzuu—a mathematically minded engineer and father of eleven children, whose sense of purpose came brilliantly alive in the small workshop of a tuberculosis sanatorium.