005. PEDAGOGY

Alt School: Did tech kill the material star?

Written by Eliot Greene

Think back to when you were a child, back to your school years. Can you remember any of the classrooms you spent hours in, reading, writing, practicing arithmetic, and memorizing state capitals, many of which you have perhaps forgotten? Think back to a teacher who stands out, kind or strict, or if you were lucky, both. Can you recall the teacher standing in front, the board covered in writing, or a room full of maps, textbooks, backpacks, worksheets, and Ticonderoga pencils? For most of us, this image is remarkably familiar despite generational differences. Such durability is the result of America’s nationalized education system, which has changed far less than many of the country’s other major institutions. Of course, the methods in the classroom have evolved, but the very format of education has changed remarkably little in the past fifty years. In the current educational environment of accountability, testing, and Common Core alignment, there is a desire to change, and around the country many different organizations are trying to modernize education for our rapidly changing world. One vision of progress is being developed by a group of Silicon Valley executives who believe that the future of education is personal, digital, and right in our backyard. They call this vision AltSchool.

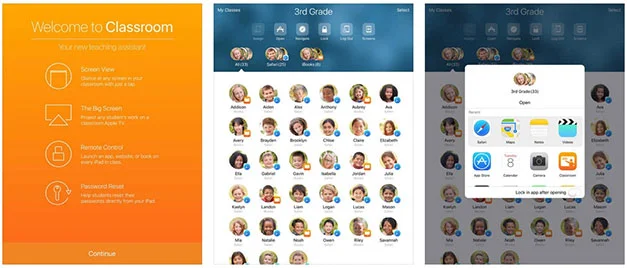

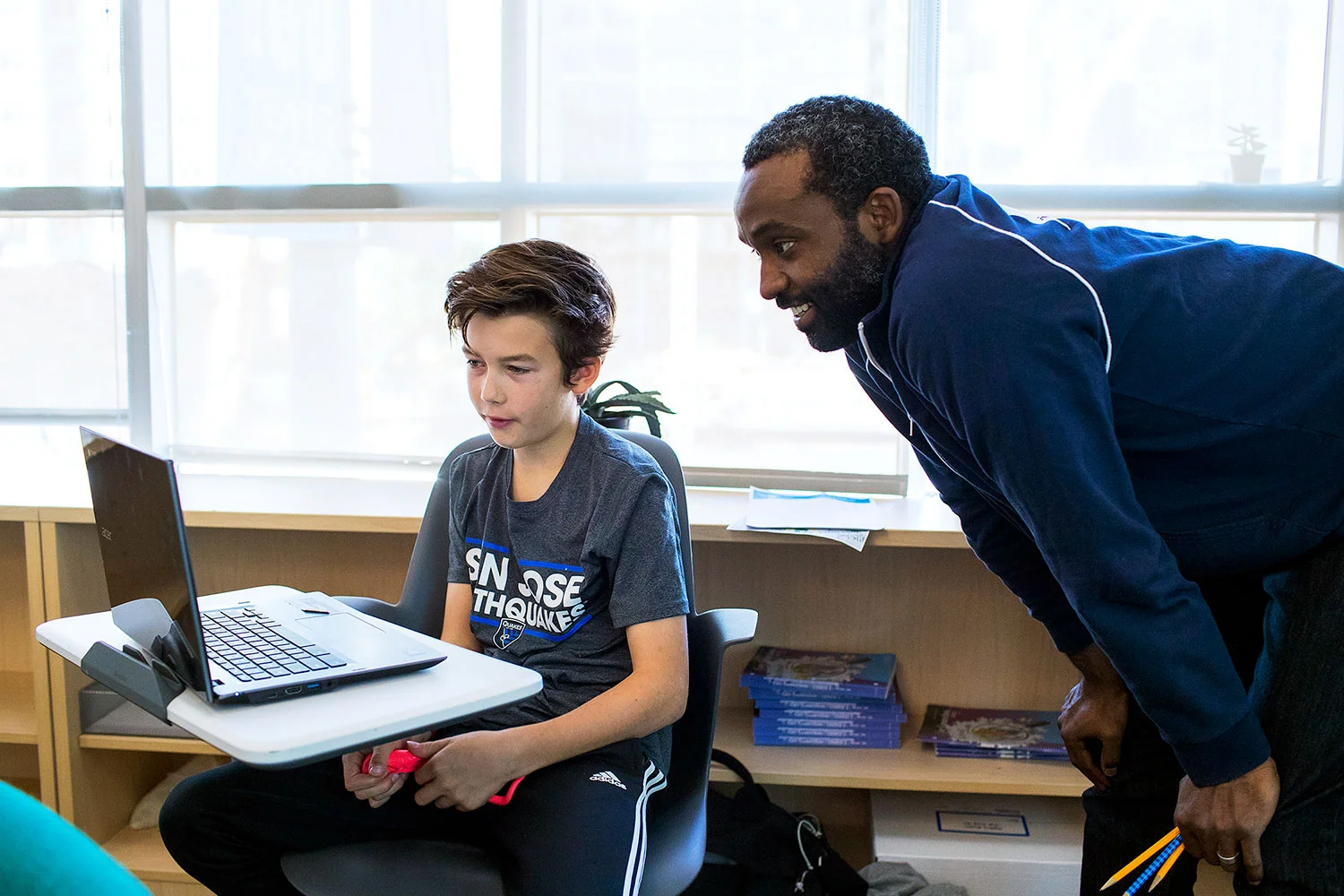

AltSchool is the brainchild of Max Ventilla, Google’s former head of personalization, who is applying big data directly to students. AltSchool’s classrooms, which resemble something out of an IKEA warehouse, are very different from the classrooms you and I remember, full of tactile learning tools to help guide us on our way. All AltSchool students are given tablet computers to work on when they enter prekindergarten, and they receive laptops as they get older. This in itself is not uncommon, but what the students do with these devices makes AltSchool unique. Teachers assign personalized work based on students’ individual learning progress, then guide them in their learning. We might think of this as bottom-up education, the unification of the Reggio Emilia approach—in which students’ interests help guide their teachers' assignments rather than the other way around—with technology. We remember school as a hierarchy in which wisdom and knowledge were passed from teacher to student. Through the personalization of education, the gulf between teacher and student is shrinking, transforming the educator into a data detective finding gaps in students’ understanding and helping them find ways to fill those gaps.

The AltSchool tool that allows this level of personalization is called “Playlist,” and one might think of it as a natural evolution of Khan Academy, a free online education platform currently utilized around the world. Students follow personalized curricula, which give instructions for both digital and physical lessons, allowing them to grow through individual assignments as well as through more long-term, project-based learning. What is especially remarkable about Playlist is the data that it can generate. A tool called the Learner Profile tracks students’ achievements daily, even hourly, assessing social and emotional skills in addition to typical academic skills, such as proficiency in reading and math. It generates visual depictions of students’ progress, highlighting areas of difficulty and allowing teachers to provide feedback within the day. This is a radical shift, as most current educators, in order to understand their students’ progress, need either to identify issues via their own assessments or to wait until August for the yearly state assessments to be returned.

AltSchool is expensive to operate, but Ventilla has raised 173 million dollars in funding, 100 million of which has been pledged by Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan. The program operates as a “micro school,” or the modern conception of the one-room schoolhouse. Class sizes are small, allowing a high level of personal attention and student independence, and partially explaining the 20-thousand-dollar price tag that comes with admission to AltSchool (which, in fairness, is far less than many other private schools ask for).

Looking to the future, AltSchool has announced the creation of AltSchool Open, a partnership with a number of other schools that utilize the same kind of Reggio Emilia, Montessori, and constructivist methodologies that drive AltSchool’s pedagogy. This branching out signals the continuation of a process that began a decade ago with Success Academy Charter Schools. Founded in 2006 in a single building, Success now operates more than forty schools in the New York City area. While Success has perhaps an opposite educational ideology (namely, a full embrace of the assessment obsession), both programs are pursuing paths toward the modernization of the United States’ educational system. Are such partnerships the beginning of a new age of privatization of the nation’s education system? Perhaps, but the utilization of technology in the classroom is something that can only continue to grow.

AltSchool’s unique vision, of a future in which students are able to learn what they love, hinges on the key elements of motivation and innate childhood curiosity. Is this enough to bring an outdated education system into the twenty-first century? Can AltSchool meet the needs of special-education classrooms across the country? Is its model sustainable in minority communities and the inner city? Does the movement away from material learning and emphasis on electronic tools help or harm our children? We do not yet know the answers to these questions, but the data is being gathered in the classrooms of the future, starting with AltSchool.