005. PEDAGOGY

Better Playgrounds, Better People?

Isamu Noguchi's Never-Built New York Playscapes

Written by Jon Earle

In 1934, Isamu Noguchi went to see Robert Moses with a radical proposal. Having learned of the parks commissioner’s plans to build hundreds of areas for children throughout New York City, Noguchi hoped to interest Moses in Play Mountain, his vision for a new kind of playground. It would contain no swing sets, sandboxes, or seesaws—and no cues for how to play on it. Instead, the sculptor’s sweeping, tiered pyramid would be a place for undirected play, a place where the imagination could run wild. No other artist in America was designing playgrounds like this one.

The meeting didn't go well. Noguchi recalled decades later: "Moses just laughed his head off and threw us out, more or less. [He] took offense at me, thought I was trying to kill people, said a playground had to be tested equipment and that New York City could not afford to test my mountain.”

Rebuffed, Noguchi turned his attention toward other projects—designing sets for Martha Graham, sculpting busts of New York's beau monde—while Moses set about building his beloved playgrounds, adding an astonishing 658 to the city landscape by 1960. Half a century later, Moses's playgrounds still predominate, even as his one-size-fits-all approach gathers dust. It seems so un-New York, but it's true—generations of kids in America's most diverse, iconoclastic city have climbed and jumped and swung exactly as Moses wanted them to. But what if things had turned out differently? What if Play Mountain and hundreds of other "adventure playgrounds"—a concept that, in all fairness to Moses, wouldn't gain traction in the United States until the late 1960s—had been built instead?

Noguchi doesn't quite entertain this speculation in A Sculptor's World, his 1968 autobiography. His actions, however, speak volumes. Over three decades, Noguchi tried to build at least four adventure playgrounds in New York City, only to be thwarted by hidebound officials and reluctant residents who feared that his proposals were too expensive, too dangerous, too inclusive, too uncontrolled—too different, in short, from what a playground was supposed to be.

That we know about Noguchi's pioneering playground work at all is due to the artist's fabulous successes—enigmatic stones, landscapes, and household items, to name a few—and his influence on other playground designers, including Richard Dattner, who built New York City's first adventure playground in 1967. And while Noguchi's playground designs appeared in major museums and art publications beginning in the 1930s, the first comprehensive retrospective was held only this year, at the Museo Tamayo in Mexico City.

Noguchi's playgrounds are as relevant today as they were decades ago, not simply because they're exceptional works of art—Noguchi considered them among his best—or because they paved the way for today's adventure playgrounds, but because they embody values that are worth taking seriously: creativity, inclusiveness, socially relevant art, and learning through play. Robert Moses may be long gone, but the tug-of-war between officials, the public, and playground designers over these values is and will always be ongoing.

Perhaps the best articulation of Noguchi's thinking on playgrounds appeared in an April 1952 ARTnews article about his work. The playground, “instead of telling the child what to do (swing here, climb there), becomes a place for endless exploration, of endless opportunity for changing play." By virtue of their ambiguity, Noguchi's play equipment and topographical forms encouraged children to invent their own games and come to their own conclusions about how to play. It was more fun that way, but there was an educational motive, too, and a utopian dream behind that. As Manuela Moscoso, curator of Noguchi's Playscapes at the Museo Tamayo, writes in the exhibition's catalog, the sculptor “viewed creative play as a way of learning about and participating in the world, emphasizing imagination, especially that of children, given that they represented the future that would be built by the fractured postwar society."

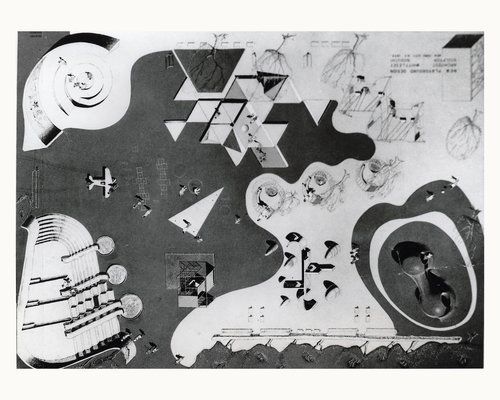

It's hard to imagine a more ideal site for a Noguchi playground than the United Nations—the embodiment of postwar international cooperation, whose headquarters is a landmark of modernist architecture. So in 1951, a philanthropist asked Noguchi to design, as the artist put it, a "new and more imaginative playground" that matched "the spirit of idealism and goodwill engendered by the UN." The resulting design was an exuberant wonderland of abstract shapes for crawling, climbing, jumping, and sliding, like a Kandinsky painting made three-dimensional. Play Mountain now appeared as a fractured, multicolored step pyramid composed of irregular triangles. Play equipment had appeared, but not the Moses kind; Noguchi's imagination had bent steel into a beehive-like jungle gym, and spread the "excess material" across the playscape. Again, Robert Moses was unimpressed: "I'm not interested in that sort of playground," he told the New York Times. “It's got to be on our plans. We know what works." The playground was never built.

From 1960 to 1965, Noguchi collaborated with architect Louis I. Kahn on a playground for Riverside Park. Though Though the project appeared 30 years after his interest in playgrounds had peaked, Noguchi once again worked tirelessly to realize his long-held vision of playgrounds as sculptural landscapes. Noguchi's close friend R. Buckminster Fuller had called for the "reintegration of the arts towards some purposeful and social end," and none of Noguchi's playgrounds came closer to combining fine art and everyday living. Every structure and space was to be multifunctional. The nursery building, for example, would be a changing station, a sun-trap in the winter, and a fountain and water area in the summer. Motifs from Play Mountain and the UN playground—triangular steps, giant slides built into mounds of earth—reappeared alongside gorgeously imagined "functional elements," such as an area for music, theater, and puppet shows.

After five years and numerous revisions in response to city and neighborhood demands, the project was killed by Mayor John Lindsay's administration, because of budgetary concerns. "Our playground took too long," Noguchi concluded glumly. He also cited antagonism from "better-advantaged" people who feared an influx of African-American and Puerto Rican children, and others who felt that a vacant lot should be used instead (Noguchi was sympathetic at first, but he later came to believe that playgrounds shouldn't be fenced in, and that some parks should become, at least in part, "play gardens"). Two years later, an adventure playground designed by Jerry Lieberman and inspired by Noguchi opened in Riverside Park, not far from the site of the abandoned project.

While other Noguchi-designed playgrounds were built across the globe, the sculptor lived to see only one playground built in the United States—in 1976 in Atlanta's Piedmont Park. By that time the artist had abandoned earth modulations in favor of specially designed equipment. The resulting playscape lacks the ambition of Play Mountain and the UN playground. A passerby might stop to admire the swing sets on jutting triangular frames, or the spiraling slide winding around a cylindrical core, or the multicolored, Tetris-like cubes. But Noguchi's garden of play-equipment curiosities is unlikely to ignite the imagination.

When it comes to Noguchi's playscapes, the whiff of "what if" is alluring but futile. Moses's 658 playgrounds were built; Noguchi's weren't. That said, his work lives on in playgrounds by Richard Dattner, Jerry Lieberman, and others who came after him. If their work transmits the values that Noguchi championed, then perhaps more adventure playgrounds will sprout from the cold concrete, and countless little New Yorkers will learn to be a bit more independent minded, creative, and experimental. A bit more rambunctious. A bit more like the shape-shifting genius—Noguchi himself.