005. PEDAGOGY

The Bamboozler: Designing for Children During the atomic age

Written by Adriana Kertzer

“If salvation and help are to come, it is from the child, for the child is the constructor of man, and so of society. The child is endowed with an inner power which can guide us to a more enlightened future. Education should no longer be mostly imparting of knowledge, but must take a new path, seeking the release of human potentialities.”

Maria Montessori

“[T]he modernist design movement contains a rich vein of warmth, humor, and avuncular spirit, and nothing illustrates this better than the furniture its adherents created for children.”

Jeffrey Head

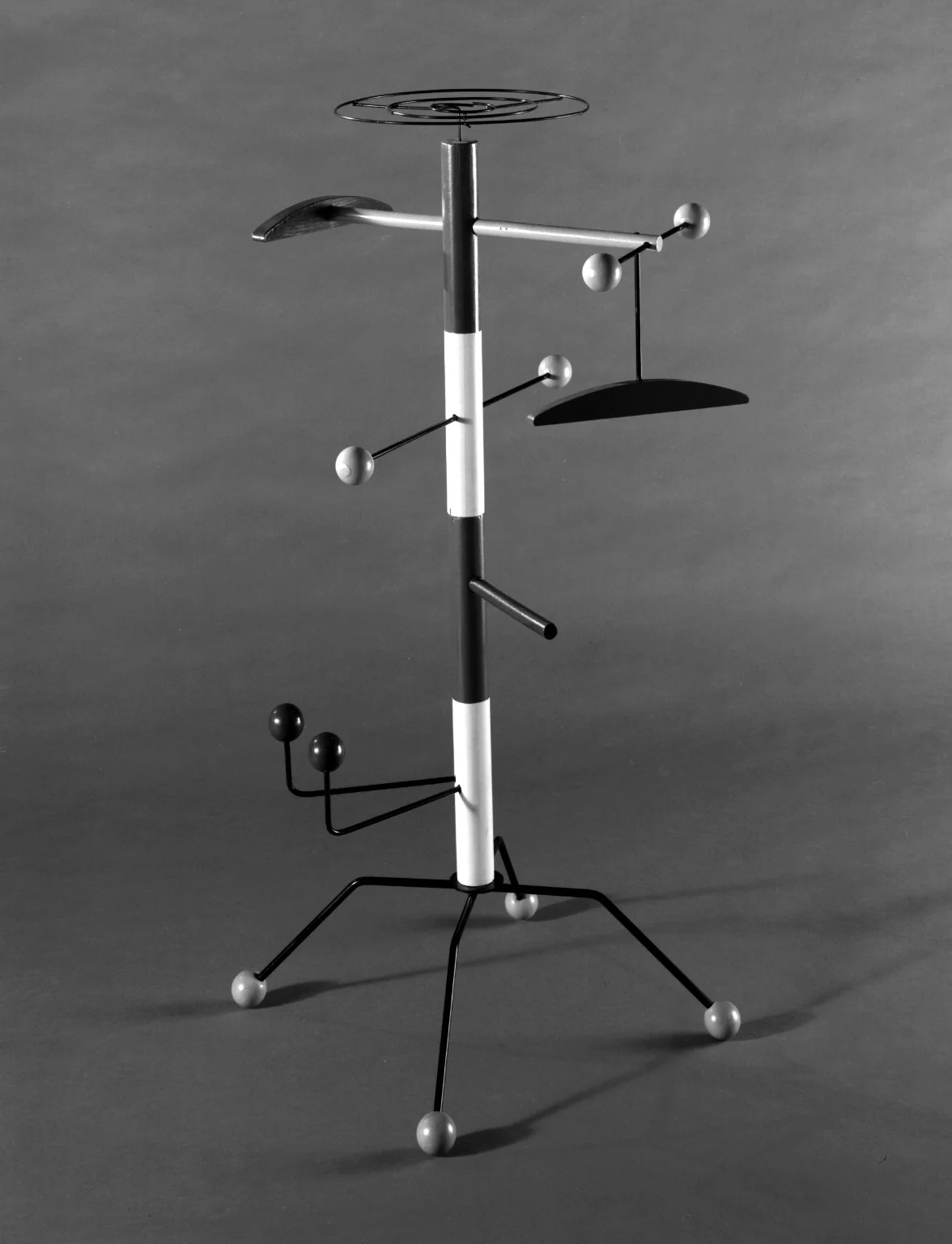

The Bamboozler, a children’s clothes tree designed by Richard Neagle, playfully evokes the molecular structures revealed by electron microscopes in the 1950s. Neagle’s objective in designing this whimsical piece was twofold: to help children transform chores (such as hanging up their clothes) into a game and to create a toy children could assemble on their own. He intended his design to help children develop self-discipline. The Bamboozler was the precursor of the Tog Tree—a children’s clothes tree produced in Italy and the United States in the 1960s—and both are examples of how children’s furniture took on a more playful spirit as the twentieth century progressed and modernism became increasingly popular. The Bamboozler also reflects how societal thinking about children changed during the twentieth century as progressive educators and sociologists challenged established notions of child development and began recognizing childhood as a stage of life during which learning could be synonymous with fun. The colored balls, cylinders, and racks of the Bamboozler can be moved, disassembled, and reassembled as the child wishes. Although by no means a literal model of molecules, atoms, or a spaceship, the Bamboozler transforms the popular scientific imagery of the 1950s into a dynamic design for children.

Demand for children’s furniture during the 1950s came from multiple sources. In describing the postwar years, Mildred Friedman observed:

At war’s end, Americans were euphoric in their hard-won victory. Returning veterans were eager to make up for lost years. There was an urgent need for housing and related consumer commodities, long unavailable, owing initially to the Great Depression and later to the war. New materials and technologies—some developed to serve wartime needs—made possible an array of fresh products and led to the ubiquity of synthetics in today’s world. A vast number of opportunities were available to young architects and industrial designers who brought “Yankee ingenuity” to a long list of postwar issues.

From 1946 to 1964, the United States witnessed the “baby boom” during which an estimated 77.3 million Americans were born. The postwar period was also marked by burgeoning economic prosperity. After years of doing without, Americans were finally able to buy cars, houses, furniture, clothes, and luxuries such as dishwashers, television sets, and stereos. Increased wealth and population also translated into more schools and hospitals throughout the country. In his article “Serious Fun,” Jeffrey Head argued that “[n]ew designs for children’s furniture often appeared as a result of such architectural commissions, when a client would specify appropriately scaled furniture to go with a structure.” Additionally, the GI Bill provided unprecedented access to housing for white veterans and led to the construction of millions of single-family homes that needed furniture.

Changing attitudes toward family life, parenting, and childhood also generated increased demand for children’s furniture. As Amy Ogata noted in her article "Building Imagination in Postwar American Children's Rooms," American houses were being designed with children in mind. According to Ogata, the values of creativity and imagination were represented in middle-class domestic interiors, and parenting, women’s, and architectural magazines fostered these ideals. In fact, “[v]irtually all of modernism’s greatest architects, designers, and manufacturers produced something for children.” As a result, “[m]any of modernism’s most engaging, innovative, and ebullient twentieth-century and contemporary furniture designs are those that were conceived for children.”

When it came to children’s furniture, designers such as Neagle had to ensure their products were “good goods” and expressed the dreams people had for their children. “In the postwar period there was a remarkable focus,” noted Friedman, “clear in retrospect, on the design of high-quality utilitarian objects.” The meaning of quality in children’s goods during the 1950s was influenced by educational theories that suggested abstract forms would stimulate a child’s imagination more than narrative toys. These ideas may have influenced Neagle’s design for the Bamboozler in 1953 or 1954. “Though production of children’s furniture increased at the turn of the twentieth century,” noted Head, “the bulk of these pieces were copies of traditional adult forms.” However, as the century progressed, “modernism cemented its place in the design universe” and societal thinking about children changed. As a result, children’s furniture became a “more playful, independent spirit, and free of past references.”

Changes in how American society viewed family life greatly influenced design for children during the 1950s. In the late 1800s, progressive theorists began challenging Victorian perceptions of children “as junior-sized versions of adults.” For example, the Austrian philosopher and architect Rudolf Steiner and the Italian physician and educator Maria Montessori proposed educational methods that treated childhood as a distinct stage of life during which learning could be stimulated in novel ways. Their methods gradually became popular around the world.

Steiner believed that the development of the imagination is essential to a good education. In a Steiner kindergarten, children play with simple, unfinished wooden toys rather than bright plastic ones, to allow their imaginations to develop. The schools have few books or computers. The Steiner educational method insists on a balance between artistic, practical, and intellectual teaching while emphasizing the development of social skills and spiritual values.

Like Steiner, Montessori believed in the value of a child’s imagination. However, her educational method arose from her beliefs that children teach themselves, that they do certain things naturally and unassisted by adults, and that the function of the environment is to allow the child to develop independence in all areas according to his or her inner psychological directives. The Montessori method is based on the doctor’s observations of “children's almost effortless ability to absorb knowledge from their surroundings, as well as their tireless interest in manipulating materials.” Montessori education emphasizes empirical learning, with a focus on real objects, and free activity within an environment tailored to the specific characteristics of children at different ages. In addition to being age appropriate, the environment should exhibit the following characteristics: construction in proportion to a child and his or her needs, beauty and harmony, order, an arrangement that facilitates movement and activity, and limitation of materials to only those that support a child's development.

The Bamboozler reveals Neagle’s desire to create not just a children’s clothes rack, but an object that would stimulate a child’s creativity and imagination. In this sense, the Bamboozler goes beyond merely satisfying demand for children’s furniture—it reflects specific ideas of how children play and learn. Its packaging and advertising described the object’s full potential. The clothes tree was sold unassembled in a box resembling the packaging of a board game. This was most likely a conscious choice on the part of the designer: marketed like a toy, it would attract children’s attention. The text that accompanied the Bamboozler reinforced the idea that assembling the object could be entertaining in itself and highlighted the object’s potential as a teaching tool:

Especially designed to help your children make a fascinating game of hanging up their clothes, and with the BAMBOOZLER it is a fascinating game. More than a clothes tree (it holds everything, hats, garments, shoes and socks), but the fun is that there is a very special place for each of these. Spread out the children’s clothes on the BAMBOOZLER and let them “pick it off the tree.” Before you know it they’ll be hanging it back on the tree—maybe with some new twists of their own, but be assured they’ll put it all back because it’s fun.

It’s even fun to play with the BAMBOOZLER—small fry might suspect it’s a convertible spaceship what with the revolving hat rack at the top. And the adjustable sliding rods lend themselves to juvenile ingenuity. The BAMBOOZLER has been carefully designed and balanced so that young Range Riders will find it quite a problem to knock it over. And with its brightly colored paint, which is by the way completely scrubbable, it’s a very exciting addition to any youngster’s room blending with all color schemes and furniture.

These descriptions reveal a belief that a child’s responsibilities could be turned into play, that the object could help a child learn how to be orderly, that a child could be creative in his or her use of the clothes tree, and that the object itself could engage a child’s imagination and attention. The text also addresses what Neagle assumed parents wanted: safety, ease of cleaning, and compatibility with a broad range of existing interior decor.

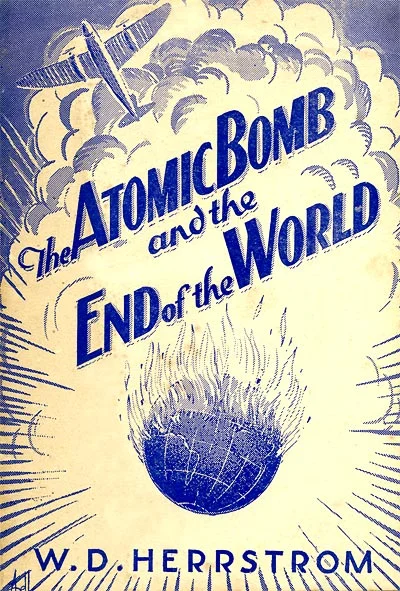

The Bamboozler embodies the values of creativity and imagination, but, as Friedman noted, “[t]he 1950s was a material decade.” It is therefore also an object designed to sell, and there was an established market for modern children’s furniture in the United States by the 1950s. The atomic discoveries of the 1940s and 1950s inspired Neagle and many of his contemporaries to create a range of household products that simultaneously communicated modernity and domesticated the genuine fear about the power of atomic energy.

Like all designers of mass-marketed goods of his time, Neagle played the role of mediator between producers and consumers, trying not only to ascertain what consumers wanted, but also to convince them to desire things they might not have imagined on their own. While nineteenth-century designers created furnishings that supported traditional domesticity, industrial designers of the early twentieth century sought to give coherent shape to mass-produced products in the machine age. Neagle’s product design spoke of the future. During the postwar years, the forms of new products—automobiles, radios, vacuum cleaners, and even children’s furniture—had to reflect modernity.

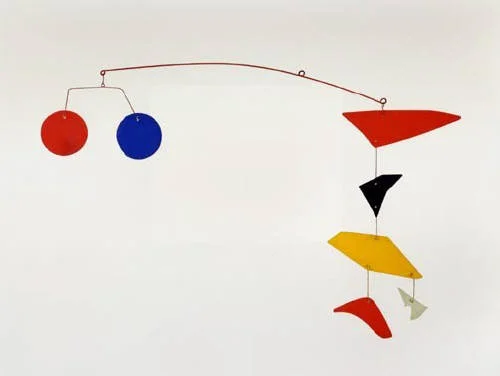

Two iconic designs, the Ball wall clock by George Nelson and the Hang-It-All rack by Ray and Charles Eames, use atomic forms similar to that of the Bamboozler. The Ball clock, sometimes called the Atomic clock, has become an icon of mid-twentieth century American design. With its rods and spheres evocative of the structure of the atom, it was the star of a line commissioned by the Howard Miller Clock Company to update its collection for a new, postwar generation of consumers. The Eames clothing rack also evokes molecular structures and, like the Bamboozler, was designed with children in mind. Its colored balls, for hanging coats and hats on, seem to move around one another as a viewer passes by. Although by no means literal models of molecules, the Hang-It-All, Ball clock, and Bamboozler transform the popular scientific imagery of the 1950s into dynamic designs.

It is not by chance that the Bamboozler looks like the toys created by the Bauhaus movement in Germany during the 1920s. At the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, Neagle studied under Rowena Reed Kostellow, one of many Bauhaus exponents who had moved to New York because of the war. Together with her husband, Reed established Pratt’s industrial design program and taught a methodology she called the “Structure of Visual Relationships.” The principles she helped formulate became the universal first year of study for all Pratt Institute art and design students, including Neagle. In an interview in 2003, Neagle described Reed as “a very, very important person in my life.” He also described how Pratt’s first-year course, taught by Reed, was based on Bauhaus ideas. It was an “introduction to formal forms, instead of copying nature and animals . . . there was a certain science to be learned, and [Reed] was responsible for this course.” In fact, although the original Bauhaus program included aspects of drawing and painting, it initially focused on craft training. Reed’s influence on Neagle’s designs is best understood when looking at children’s furniture created by the Bauhaus school. The basic geometric shapes and primary colors used by Alma Buscher and Peter Keler resemble those of the Bamboozler. Neagle believed:

the use of a bright color on a product should be limited to calling attention to that part or control or as an accent to a form. Many colors on a single product produces “visual pollution,” just as too many patterns and colors ruin an interior design.

The Bamboozler reflects these principles. The central cylindrical pole is constructed of four equally sized wooden parts, alternating red and white; the metal legs, horizontal posts, and top rack are painted black; and the spherical knobs attached to the legs and posts, the wooden dowels, and the two wedge-shaped “hanger” pieces are painted yellow, blue, and red. Like the toys made by Bauhaus designers, the Bamboozler relied on abstraction, shapes formed from elemental building blocks, and primary colors.

The shape, materials, and color of the Bamboozler are also reminiscent of the works of Alexander Calder, whom Neagle placed at the top of a list entitled “The following ‘masters’ have been my greatest influences.” The extremely popular American sculptor is recognized as the “inventor of the delightful, softly moving work of art known as the mobile.” From the mid-1930s to the mid-1950s he also experimented with other forms, producing such works as wood-and-wire constructions that looked like mobiles but did not move, jewelry, gouache paintings, and sheet-metal sculptures. In fact, the Bamboozler is similar to Calder’s Morning Star (1943), a sculpture of sheet metal, wire, wood, and paint. Throughout his career, “designers of new airports, corporate headquarters, museums, and plazas throughout the world were demanding large pieces and Calder became a popular choice to supply them.” It is therefore almost certain that Neagle was exposed to Calder’s works, through magazines or in New York museums or the many other buildings in which they were displayed.

The desire to domesticate the atomic reality of the 1950s might have been for Neagle the result of actual experiences with the Manhattan Project. He enlisted in the army on January 25, 1943, and during his three and a half years of service, he eventually flew B-29 bombers for the air force. Notably, he was stationed on Tinian, one of the three principal islands of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. It was from this base that the United States launched the atomic bomb attacks on Japan in 1945.

When World War II ended, the United States found its mainland physically unscathed and its economy revved up by massive military spending. But the atomic bomb was now a reality, and veterans still had to process their war experiences. When Neagle arrived in New York after the war, he found a city that “had become the capital of this new world power,” as America gained affluence and primacy. After years of wartime rationing, people wanted to consume. For designers during the late 1940s and ’50s, this meant there were more things to create. Yet it is important to highlight that “[i]t was a slow, uphill struggle for contemporary furniture designed for the home, first reluctantly admired and finally embraced by a small number of adventurous cognoscenti.” When Neagle created and sold the Bamboozler, living rooms of suburban homes were mostly “filled with unremarkable assortments of furniture in pseudohistorical styles made in Grand Rapids”—conformity was the name of the game. As a result, the 1950s were probably challenging years for Neagle, both as a veteran who had been a bomber during the war and as a modern designer.

Any discussion of the importance of midcentury modern children’s furniture such as the Bamboozler is made even more relevant given the fact that recently, several companies have produced kid-size models of iconic modern furniture. For example, Knoll now offers a child’s Mies van der Rohe Barcelona chair and stool, as well as a Saarinen Womb chair and ottoman. These reimagined classics are materially identical to their full-size counterparts. In the 1950s, “a new kind of domestic furniture was shown in American museums and available in the marketplace. It was portable, small-scale, and designed to withstand the onslaught of tiny peanut-butter-and-jelly-covered hands and the cats and dogs essential to a happy, child-oriented suburban home of that era.” The scrubbable Bamboozler would probably be a magnet for design-conscious parents today, due to both its commitment to children’s imagination and its incredible design.