003. ICONS

transatlantic postmodernism / eames & berthier

Written by Meg Czaja

For some people, to focus on a designer’s work on children’s furniture is to diminish the importance of that designer’s overall career; by its very nature children’s furniture is diminutive. Some icons’ work in children’s design is downplayed almost to nonexistence. Marcel Breuer, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, and Charles and Ray Eames, for example, all explored the world of the child, yet their contributions are either overshadowed by their other works or rarely discussed.

Before World War II, children’s furniture reflected the prevailing styles of the time, and designers often failed to consider the child on his or her own terms; a child’s desires, limitations, and play patterns were not reflected in the scaled-down versions of adult furniture meant for children. The postwar period demanded a realignment of design principles. Design was now for living and leisure, as opposed to fulfilling wartime requirements; the center of our world was moving back home from the front. Successful design now met the practical needs of ordinary people in aesthetically pleasing ways. Sensing this, American designers such as the Eameses and French designers such as Marc Berthier began to design products and spaces with fresh, childlike eyes.

MOLDED FORMS

As the world shifted to peacetime manufacturing in the late 1940s, designers began to repurpose and capitalize on the innovative manufacturing processes and materials developed during World War II. In 1945, Charles and Ray Eames created a series of single-piece plywood chairs and tables for children; they were manufactured by the Evans Company, a wartime producer of wood products (most notably bent-plywood leg splints). This children’s collection was one of the first that focused on both style and substance. A single piece of colored plywood appears as if it were a drop cloth draped and cut to form a miniature chair. The organic softness of the chair’s curves is shared by other Eames chairs of the time, including the DCW and LCW, though the children’s chair is simpler than its adult counterparts. It was engineered not only to withstand but to encourage play. Though immensely strong, it is lightweight enough to be moved by a child, and its appeal is enhanced by a whimsical folk-inspired heart-shaped cutout in the backrest.

Another wartime innovation embraced by postwar designers was fiberglass-reinforced plastic, which was a perfect material for the construction of affordable furniture. First developed by the United States Army and adapted by the Eameses for their entry to the Museum of Modern Art’s International Competition for Low-Cost Furniture Design, it was a versatile and durable material with pleasing tactile qualities. And though upfront tooling costs were high, the Eameses hoped that mass production of the material would allow them to “get the most of the best to the greatest number of people for the least.” Their molded-plastic shell chair is arguably one of the most recognizable pieces of twentieth-century furniture.

Fiberglass was also the material of choice for Marc Berthier’s 1970s children’s furniture collection, Ozoo. The Ozoo chair and the Eameses’ plywood children’s chair were both constructed of single sheets of material molded and cut to form. However, where the Eames chair had tapered, sculpted legs and a curved seat and back that embodied an arts-and-crafts aesthetic, Berthier’s streamlined, more geometric fiberglass forms reflected the pop art of the 1960s and ’70s. A pronounced lip on the Ozoo chair’s backrest remains untrimmed, as if to announce its molded origin, while also providing rigidity and stability for the backrest and legs. The seat extends downward into thin but stable L-profile legs, a detail matched on the accompanying desk. The desk demonstrates the utility of molded materials even further, incorporating a trough-like channel and cupholders that evoke a melamine serving tray. The glossy, monochromatic field of neon color achieves contrast through the shadows produced in its negative spaces; Berthier would revisit this aesthetic later in his career with the Tykho radio, the buttons and joystick-like antenna of which protrude from a monochromatic skin. The overall lightness of the Ozoo collection remains a prominent characteristic of Berthier’s work, and can be seen in the products of his contemporary studio, Elium.

MODULARITY AND DESIGNING FOR EDUCATION

It seems natural that in the aftermath of war, designers would be drawn to the innocence and wonder of childhood—not only embracing it, but even allowing the child to become the designer. This approach can be seen in the many construction- and craft-based toys of the postwar period, which were designed in part to combat the rise of consumerism and to reflect the results of new research by educators, child psychologists, and designers. Modularity became a regular feature of toys and furniture; construction systems, for instance, allowed children to create functional spaces by manipulating a variety of modular components.

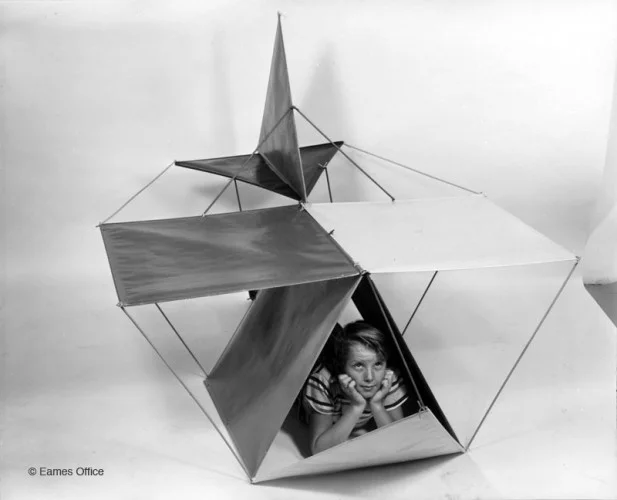

Designed according to such new principles, Ray and Charles Eames’s Toy was a kit composed of dowels and brightly colored panels that could be assembled into various configurations. The green, yellow, blue, red, magenta, and black triangular and rectangular panels transformed into abstract, Memphis Group–style geodesic spaces through a simple notched-dowel system. The infinite possibilities of these loose parts made the Toy a tool for simultaneous play and education.

Ten years after the launch of Ozoo, Marc Berthier, too, implemented modularity in his child design. In a contest sponsored by the Centre de Création Industrielle at the Centre Georges Pompidou’s inaugural exhibition in 1977, Berthier took the top prize with Mecanotube, a versatile system of materials adaptable to many spaces and environments and limited only by the needs and imaginations of its users. Mecanotube's yellow bent-metal tubes with rubber feet and eraser-pink joints resembled a set of oversized pencils, and could be combined with white melamine panels and assembled like an Erector Set, into desks with partitions and shelves. Red powder-coated baskets could be used for additional storage. The included chair featured a bent-tube frame with a triangular base, and its seat and back were composed of a single piece of bent plywood in primary colors. Berthier designed the chair to be adjustable, so that it could grow with a child, but also accommodate an adult.

Through creative use of new materials and manufacturing processes and a fascination with the worldview of children, the Eameses and Marc Berthier created functional products that opened up infinite spaces for children. The postwar paradigm shift demanded that design meet the practical needs of ordinary people in pleasing ways, and though forays into the world of child design are sometimes downplayed, some of the most important designers have unreservedly applied their skills to meeting the practical needs of people of all ages.