003. ICONS

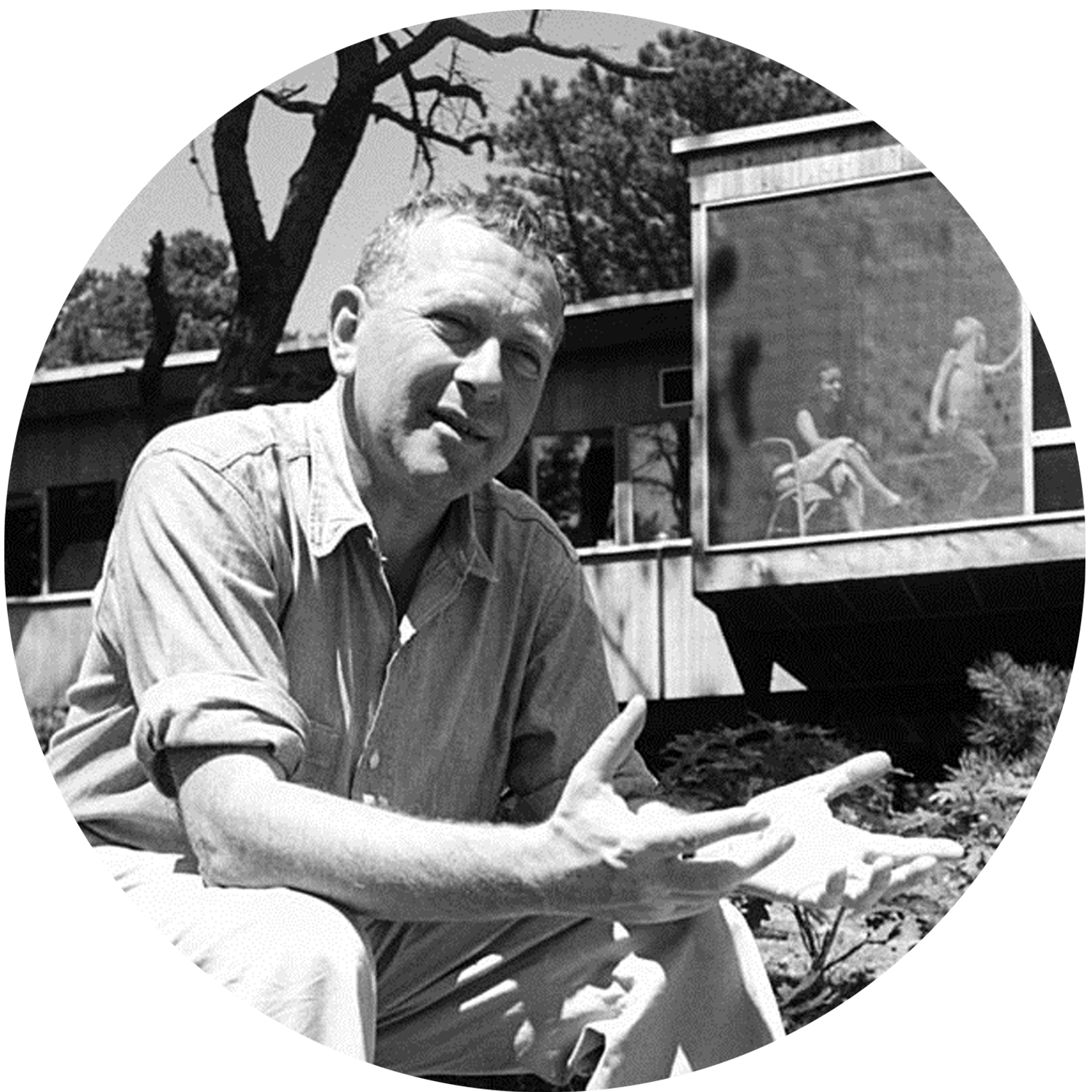

pierre paulin

Written by Zachary Vigna

There are three basic routes to designing furniture for children. The first and simplest is to reduce the proportions of an adult-sized item. We can consider this a top-down method, and it is based on an understanding that the physical needs of children are largely similar to those of adults and require little if any special attention. The second route can be considered a bottom-up method, and it involves disregarding the needs and preferences of adults in order to produce an object specifically for children. Furniture designed by this route often incorporates elements meant to allow for play or promote learning experiences, making them specialty objects. The third route can be seen as avoiding the subject altogether, but it is subtler than that; it involves designing furniture that appeals to children and adults equally. If the first method is the simplest and the second is the most specialized, the third is the most democratic; a facility with the democratic was one of designer Pierre Paulin’s greatest strengths.

Pierre Paulin was born in Paris in 1927, a year after Marcel Breuer’s completion of the Wassily chair, too late to participate in the modernist movements that first raised direct questions about form and materiality in furniture design, but late enough to apply lessons learned from Breuer and Ray and Charles Eames firmly and precisely during the advent of postmodernism and “pop” (Andy Warhol was born a year later). The two greatest influences in Paulin’s early aesthetic development were his uncle Georges Paulin and great-uncle Freddy Stoll. Georges’s crowning achievement was his design of a tubular-steel-based retractable roof that, once sold to Puegeot, began appearing on roadsters all over the world. His gift to the young Pierre was a love of automotive design and an affection for tubular steel that reflected Breuer’s, which itself was owed to the bicycle industry. Freddy was a sculptor, and it was through his influence that Pierre chose to attend the École Camondo and learn stone carving.

A debilitating injury to Paulin’s right arm prevented him from becoming the sculptor he’d wanted to be, but he was able to apply his training in a new direction: furniture design. Furniture could be sculptural, but it couldn’t be art, and Paulin began a rigorous study of how to optimize the functional characteristics of furniture, the primary one being the production of comfort. While working for a series of firms, most notably Thonet and Artifort, he experimented with forms and materials in a pursuit of comfort and a conscious rejection of accepted approaches. The resulting designs, although heavily influenced by the Eameses at the theoretical level, are noteworthy in being both visually striking and utilitarian. The experience of looking at a Pierre Paulin design is similar to that of looking at a Constantin Brancusi sculpture—design historian Catherine Geel has noted, “For Pierre, an object had to be beautiful in 360 degrees”—but the experience of sitting on one is an experience of sumptuousness.

Paulin’s greatest breakthrough was the Mushroom chair of 1959. Despite numerous widenings of the definition of furniture throughout the periods of modernist activity—especially those made by Marcel Breuer, Eero Saarinen, and the Eameses—in 1959 a chair was still immediately identifiable as a chair. By stretching swimsuit material over a tubular-steel frame padded with Pirelli foam rubber, Paulin confronted the materiality of furniture as directly as Breuer had with his introduction of tubular steel through the Wassily chair. The resulting form, vaguely reminiscent of a mushroom—although Paulin would always insist that it be called the F560—was sculptural, unique, and above all, comfortable.

To a viewer today, however, especially one unaware of the Mushroom chair’s historical significance, its most prominent characteristic is likely to be its playfulness. It is brightly colored, soft, and inviting; it looks cuddly. Most of the celebrated Paulin designs to follow, notably the Orange Slice chair and the Tongue chair, would share this characteristic, causing them to become linked with the youth culture of the Swinging Sixties and the Pop Art movement. In the spring 2008 design supplement of The New York Times magazine, Li Edelkoort described the world of Pierre Paulin as “optimistic and playful,” with the designer “kneading matter like a child uses Play-Doh and coloring in surfaces with flat, fast and fashionable markers.”

There certainly is something childlike about Paulin’s designs (despite his being, by all accounts, cold and ascetic in his personal life), and this is how he achieved the third method of children’s design. In an article about jewelry designer Cora Sheibani in the December 2013/January 2014 issue of New York magazine, Nancy MacDonnell describes Sheibani’s home as “child-friendly, at once vivid and serene. . . . Unfinished Lego sculptures are scattered on Marc Newson chairs” near “the giant Pierre Paulin sofa.”

It is natural that his designs should appeal to children, for them to deposit their toys in front of it, and Benjamin Paulin, Pierre’s son, agrees. Just before Pierre died in 2009, Benjamin founded Paulin, Paulin, Paulin, a firm dedicated to continuing Pierre’s legacy. While he was giving an interview for a March 2017 article that appeared in South China Morning Post and the interviewer noted that his children were climbing on priceless Pierre Paulin designs, he explained, “It’s what it was designed for. . . This is part of the responsibility we have, to help people understand the spirit of my father’s design.”

Although Paulin continued to work until his death, his designs had fallen out of favor by the 1990s. They had been created carefully and democratically, inviting everyone—adults as well as children—to feel comfort and a sense of playfulness, but they were too closely linked with the Pop Art generation for the preferences of Generation X. Tastes ebb and flow, and his designs, partly through the efforts of Paulin, Paulin, Paulin; partly through a 2016 retrospective at the Centre Georges Pompidou; and partly due to the current widespread rise in the popularity of midcentury modern design, have been receiving fresh adulation. One effect of the resurgence of Pierre Poulin is that Artifort, the company that produced his Mushroom chair in 1960, has issued a Mushroom Junior chair and an Orange Slice Junior chair, both scaled down versions of the originals.

Pierre Paulin has posthumously crossed over from the third route to the first route of children’s design.