005. Pedagogy

Kindergarten Architecture and the Developing Child

Written by Ray Hu

The history of designing spaces for children to grow and learn can be traced alongside the birth and evolution of early-childhood education beginning at the turn of the last century. Following the two world wars, school teachers and architects began to rethink traditional learning spaces and build facilities according to modernist design principles and new educational theories. Current legislation guaranteeing kindergarten and day care placement in countries such as Germany and Japan can be traced back to the recent global economic recession. But considering that these educational facilities serve hundreds, if not thousands, of users—children and adults alike—they should also be regarded as an architectural investment to match a societal one. Examples such as a fifty-year-old Dutch Montessori school and a Japanese firm admirably rising to the challenge of growing demand for kindergartens show how context and culture inform early-childhood architecture, which in turn reflects how nations look to improve their education systems in the current century.

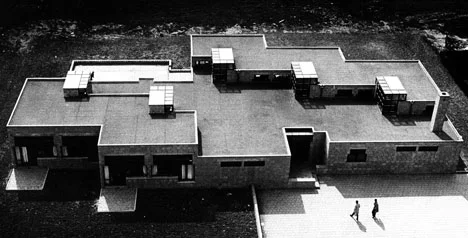

One of the most well-known and widely practiced approaches to early-childhood education is the Montessori model. Perhaps the single most significant architect designing according to the educational principles hails from the Netherlands, which boasted some two-hundred Montessori schools by the 1930s. Maria Montessori herself settled there shortly after the Association Montessori Internationale moved to Amsterdam in 1935, and she remained there for the better part of the last sixteen years of her life. Born in 1932, Herman Hertzberger was among the countless beneficiaries of Montessori’s methodologies, receiving a full fourteen-year education according to the Italian physician’s model of schooling free from restrictions and focusing on social and physical childhood development. Hertzberger subsequently studied architecture at the Technical University in Delft and launched his practice by constructing a Montessori school there. Designed as a series of L-shaped classrooms clustered around a central corridor, the modest Montessori School opened in 1966 with six rooms, gradually doubling with the addition of more quasi-modular rooms over the course of the ensuing decade and a half.

Hertzberger has since designed dozens of education spaces from dormitories to research facilities, including additional Montessori schools in Amsterdam. But, in some ways, his passion for education epitomizes a broader trend in midcentury Holland of building hundreds of playgrounds throughout Amsterdam as a gesture of urban renewal in the postwar period. Hailed today as an elder statesman of Dutch late modernism, Hertzberger continues to champion a fundamentally humanist approach to modern architecture as practitioner and professor, summarizing his philosophy in terms of “human dignity” and tellingly citing Harold and the Purple Crayon, the children’s book in which a toddler draws his own world, as an allegory for childhood pedagogy.

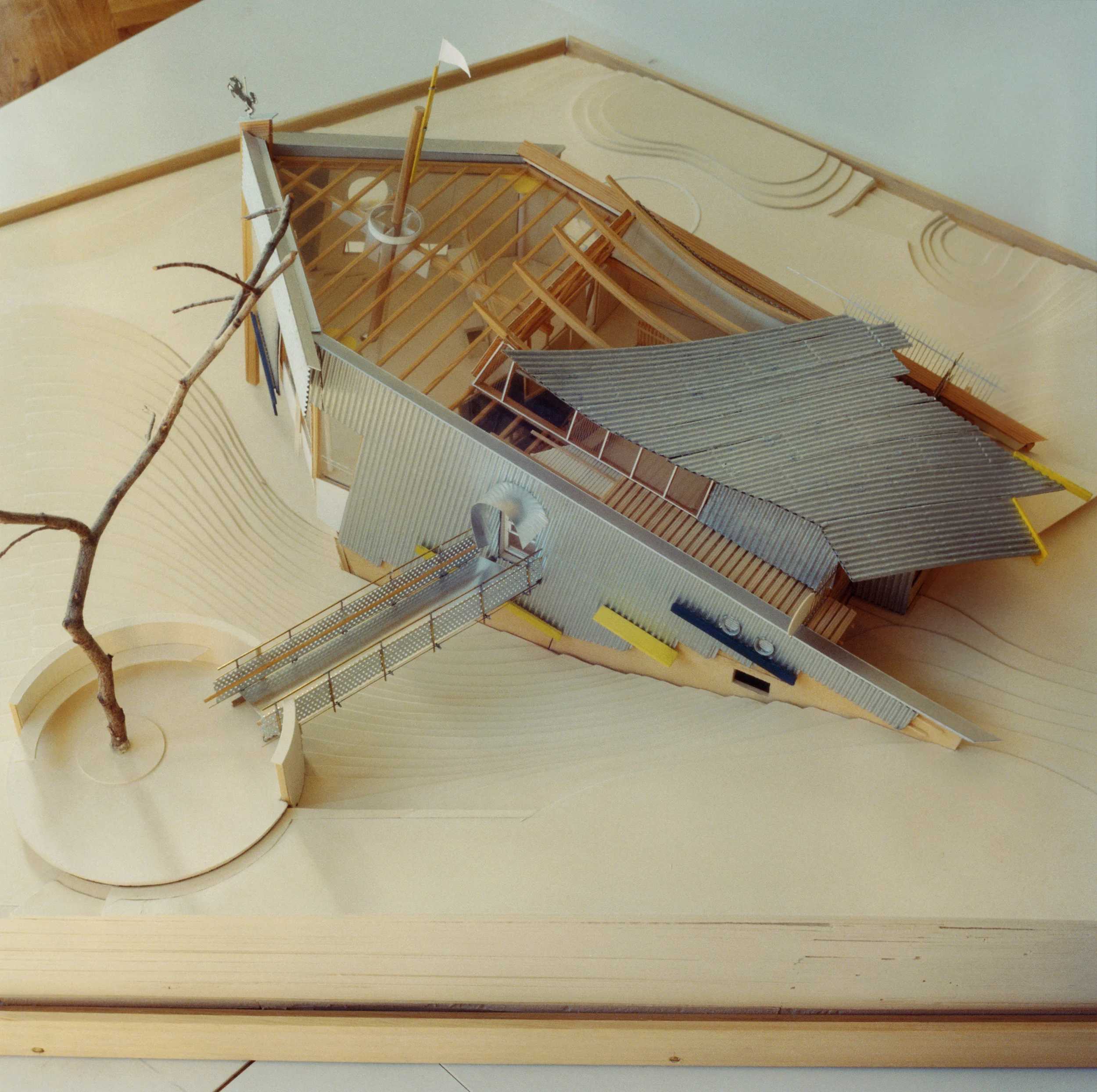

Outdoor space is all but universally regarded as an essential element of any early-childhood facility and outdoor play is chief among the tenets of pedagogues from Jean-JacquesRousseau to Friedrich Froebel, who coined the term “kindergarten” in 1837. German designer Günter Behnisch had nearly fifty schools to his name by the time he was tapped to design a playful kindergarten incongruously nestled in the rolling hills of Stuttgart, where his eponymous firm was based. Controversial since its completion in 1990, Luginsland Kindergarten resembles a ship run aground in the quiet suburb.

Like an overgrown adventure playground, the relatively compact, two-story, 3,400-square-foot edifice rises to a prow of an apex—the pentagonal plan reads like a gabled elevation—clad predominantly in corrugated sheets. Its asymmetrical facades are punctuated with both rectangular and round windows, which invariably read like oversized portholes in the vertical ripples of its hull, while a kind of gangplank spans the slope at the main entrance. Only the rear facade is rendered in horizontal timber slats, at once the starboard and a kind of upended deck; one elevation counterclockwise, the south facade is outfitted with retractable exterior curtains that allude to sails. Inside, the unconventional volumes follow from the angles of the exterior, such that the slanting plywood walls and oddly canted windows yield several intimate child-scaled nooks and crannies.

Expansion is one thing, but scalability is paramount, especially in light of a recent surge in demand for day care centers throughout Germany. In August 2013, the Bundestag passed legislation that guaranteed the right to placement in a Kita—short for "Kindertagesstätte," or "nursery"—for children as young as twelve months (previously guaranteed at age three). Municipalities scrambled to accommodate; makeshift solutions included converting vacated storefronts of a national chain that had recently gone bankrupt, as well as costly temporary buildings. The legislation originated in Eastern Germany, which has long guaranteed Kita placement for children starting at age one—the upshot of socialist policies encouraging women to work—and has fared better for it. But considering that Germany has one of the lowest birthrates in Europe, access to quality childcare looms large on the national agenda.

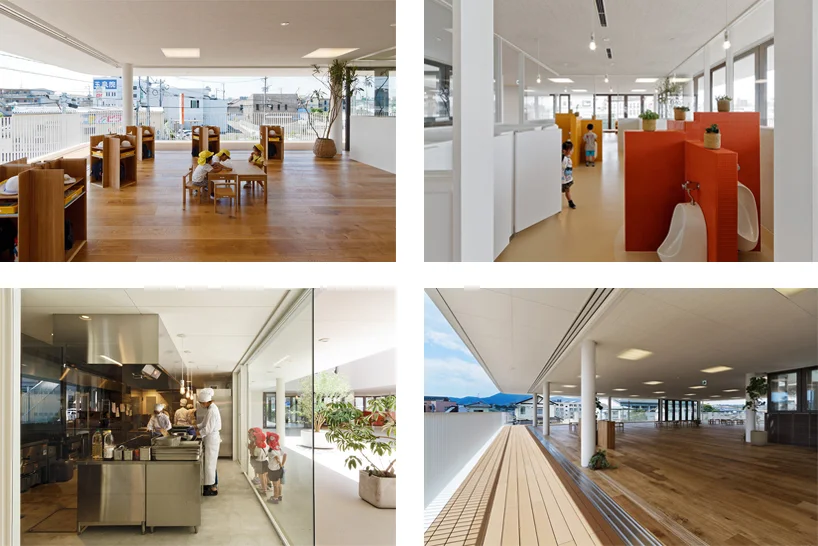

The day care crisis is not exclusive to Germany: perhaps more salient is the situation in Japan, where the 2008 recession spurred an uptick in working mothers. As waiting lists for municipal nurseries, day care centers, and kindergartens have ballooned to tens of thousands of young children, the government has been quickly piloting hybrid early-childhood care centers known as kodomoen. While supply remains woefully short of demand, Atsugi-based firm Hibinosekkei+Youji no Shiro has carved a niche as early-childhood architecture specialists, boasting a portfolio of some 350 hoikuen (day nurseries), yochien (kindergartens), and kodomoen as diverse as they are consistently excellently designed.

The clean modernist lines, child-scaled spaces, and bold colors may be typical of successful kindergartens all over the world, but features such as engawa, a kind of traditional Japanese veranda, impart a subtle sense of cultural specificity to Hibinosekkei+Youji no Shiro’s work. The principle of a porous, extended transition between interior and exterior—a time-honored means of climate control in the humid coastal cities of Japan—is radically realized in the recently completed D1 kindergarten and nursery, a dynamic school that can be adapted for a wide variety of activities. Located in the southern city of Kumamoto, the two-story school looks something like Le Corbusier's Dom-Ino house turned inside out: a rectangular plan overhangs a four-by-five grid of evenly spaced piloti, yielding a wraparound arcade on the ground floor and corresponding balcony above. A central atrium can be converted into an open-air courtyard thanks to a retractable roof; when left open to the rain, this area is expressly designed to form a shallow pool. The kindergarten's sliding doors—a contemporary nod to the shoji screens of traditional Japanese architecture—are particularly noteworthy. More generally known as tategu, these movable doors and windows allow for more than half of the building to be open to the outdoors.

Schools can represent not only design concepts, notes Sam Jacob, director of the London architecture studio FAT, but also ideas about how “society should be organized.” They are “microcosms of ideal forms of society” or “scale models”—literally at times—of the societies to which they belong. Considering that departments of education (or their equivalents) mandate only safety guidelines in their building codes, the actual designs of schools typically remain an afterthought in the face of more pressing concerns, such as staff and funding. Earlier this year, London-based architect Asif Khan unveiled a modest playground project at Chisenhale Primary School, which his children attend. Khan provided his services pro bono, and, with donated materials, created an elevated timber structure. The locales and cultures where architecturally noteworthy schools might be found are those that value education, and design is just one part of the picture. Not every school can boast an emerging architectural talent like Khan among its parents, but every architect has gone to kindergarten, which should be reason enough for every school to be well designed.