001. LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Material and the MODERN CHILD

Written by Lora Appleton

Material is the foundation from which all objects originate. It is through material that we first connect with an object via sight and touch. It is how we register the history of an object, how we explore the designer's mission in creating even the simplest and most functional items in our lives. Is this chair comfortable? Will it function in the way I need it to, or do I want to avoid it? A designer's material choices help answer these questions and invite or discourage interaction with an object. Hardwoods, concrete, and stone may all share some of the same strict qualities, but wood can be warm, stone cool, and concrete rough; each sensation inspires a sense memory and often a nostalgic reaction. Material gives access to an item's history and provenance, and therefore is the primary source of information in design.

Imagine a child’s mind, still developing, with limited context, yet with a boundless, uninhibited imagination, and what happens when the child touches a new material for the first time. They experience wonder, curiosity, excitement, and more. I recall my own child’s fascination with common plaster. He had no context for it, but he knew he badly wanted to work with it. He noted the texture and asked how he could build or create art with it. After a lengthy discussion, he began his own rudimentary research about the many ways it's used: in the home, in medicine, in art, in architecture, and beyond. My son is not alone. The materials we all encounter in our environment connect us to the outside world as we learn how and by whom things are made. Investigation into material is a perfect way for a developing child to think about his or her place in the world and the way our world grows around us.

For designers and makers material choices are a calling card. These choices express their point of view, inspirations, and motivations. Material is the clear center of design, and its special importance in child design cannot be overstated. Originally, the materials used in child design were chosen based on accessibility—both of the material itself and of the machines that could be used to manipulate it. Soon, certain materials became more "acceptable" than others for the modern growing child, and these materials—many of them extremely experimental, such as tubular steel and cellular cardboard—began predominating. From the 1920s to the '40s, wood forms predominated. Formal experimentation and simplicity of materials and production were emphasized, and experimentation was most often found in the choices of paint and lacquer or additions of leather or textile seating. In the 1960s and '70s plastics dominated the child design landscape, with designers such as Marc Berthier and Verner Panton creating children’s collections in molded plastics such as polyurethane. Through the 1980s and '90s there was a return to simplicity in material choices, with painted wooden furniture predominating—although there was still a strong focus on new forms. Cutout shapes were incorporated to inject a sense of play, whimsy, and nostalgia directly into designs for children.

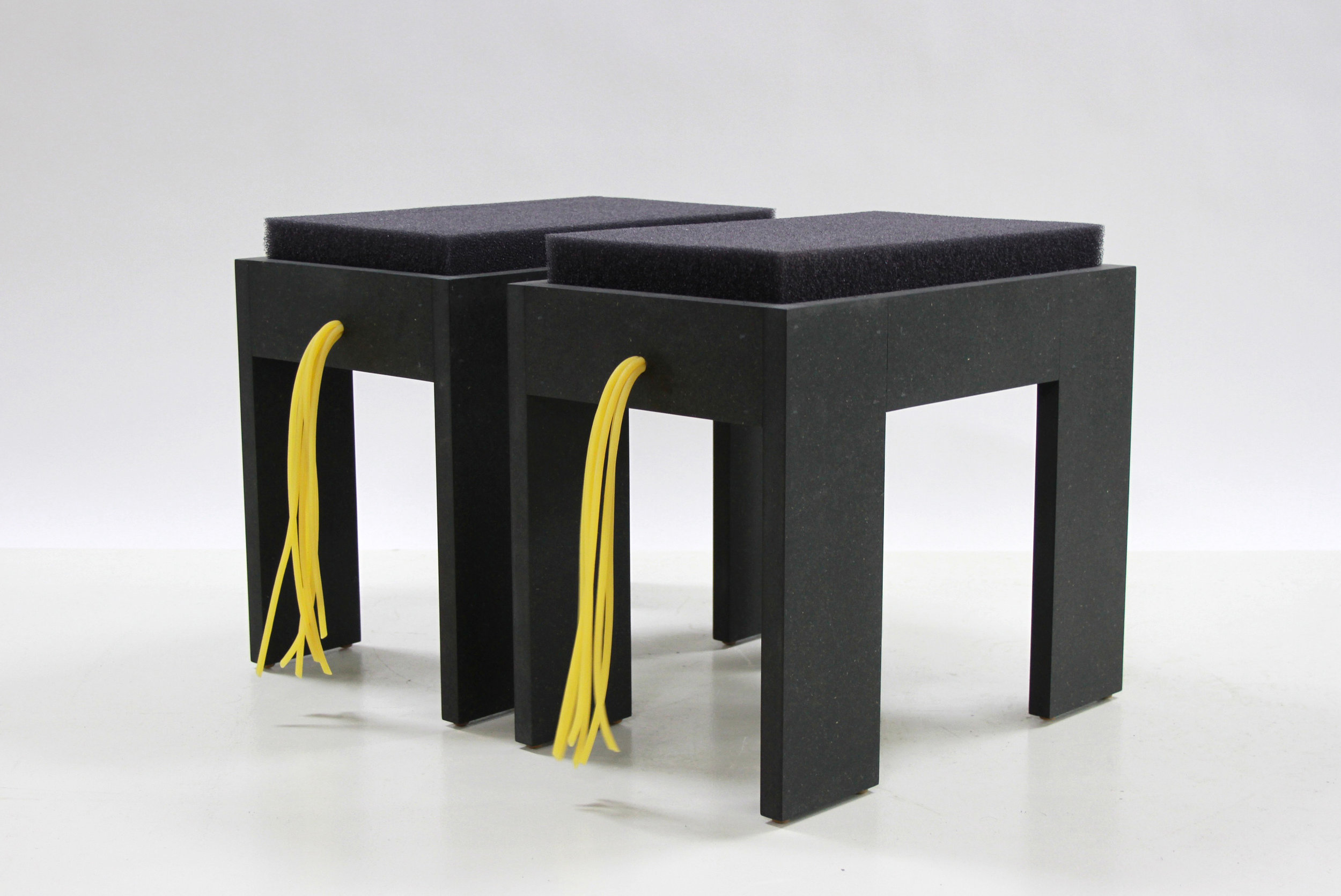

In 2016 we find ourselves again in a material-focused experimental time. Children’s designers and curators are drawn to industrial and recycled materials, including concrete, foam, industrial rubber, wastepaper, recycled paper, repurposed construction scraps, and new types of engineered fibers and mixes that allow innovative ways of designing and manufacturing furniture for children. Progressive designers such as Kwangho Lee, Wintercheck Factory, Piet Hein Eek, and Bobbles are pushing the limits of materials sourcing for use in child design. Not every children's designer, however, can be or chooses to be experimental with material. The current landscape in furniture design for children is still basic in construction and material choices. There is an incredible variety of lesser woods, faux woods, plastics, mass-manufactured metals, and fiberboard. These exist because consumers have consistently wanted them, believing them, accurately or not, to be indestructible, inexpensive, and safe. Treating children’s furniture as disposable is passé. As more young families are coming to value design and rejecting big-box brands, we are seeing more creativity and sustainability in this industry. New materials surprise us and encourage us all to learn and ask questions, while filling our homes with heirlooms for the next generation. As we move toward the future, it is essential that we not lose our spirit of experimentation. We must consider what is best not only for our children, but for our planet, our economy, and our children's children.