006. INSPIRATION

Porky Hefer's Utopian Tension

Written by Zachary Vigna

When Porky Hefer ended a sixteen-year career in advertising in 2007 to launch the creative-consulting firm Animal Farm and focus his professional attention entirely on art and design, his work immediately began expressing something of the utopian, with a sense of idealism and optimism. With this in view, his inclusion as South Africa’s representative in this year’s London Design Biennale, which wrapped up in September, was apposite: The fair’s stated theme, in celebration of the five hundredth anniversary of Thomas More’s magnum opus, was “Utopia by Design.”

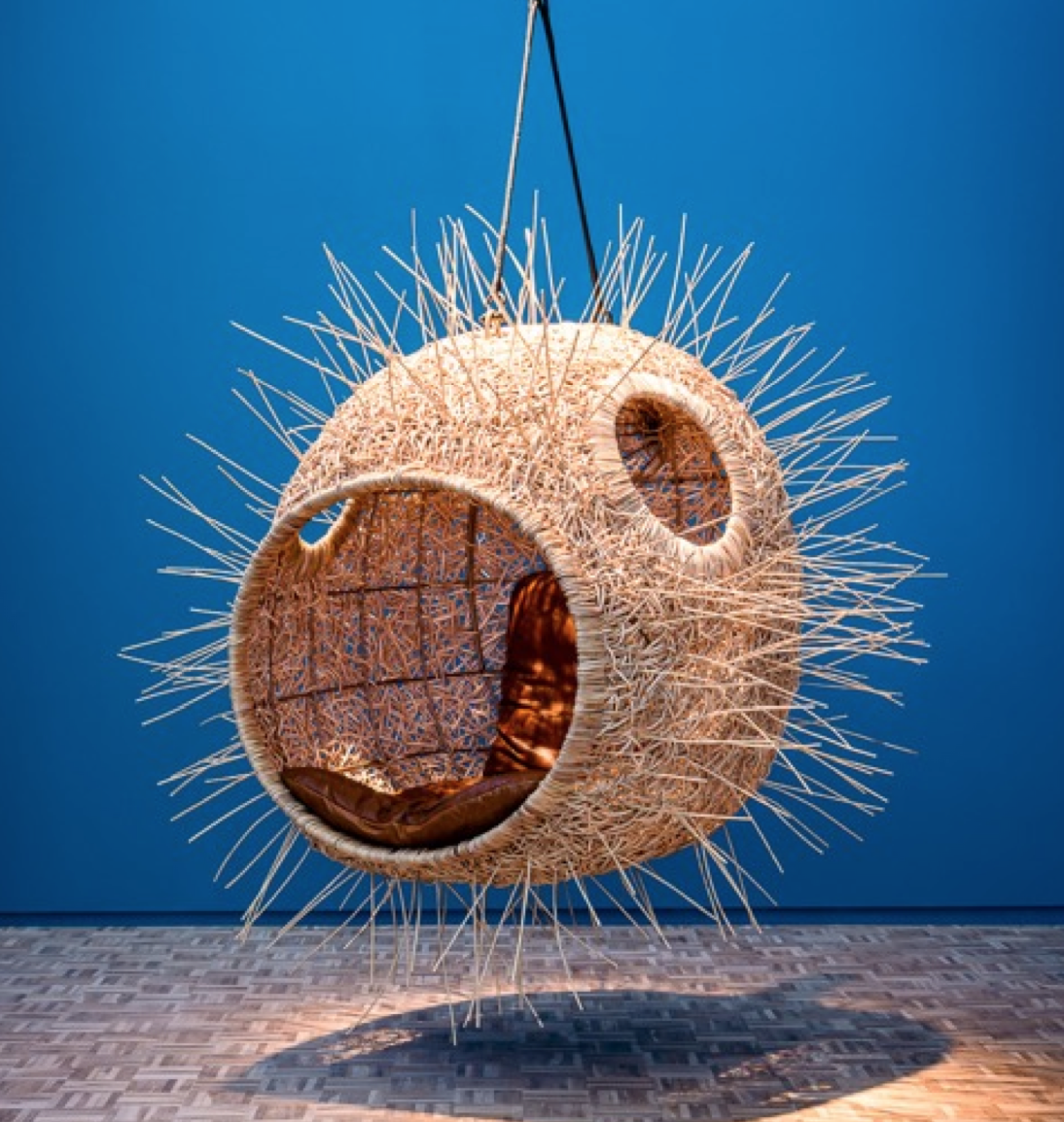

Idealism and the utopian come through most strongly in the pieces for which the designer is best known, his nests—objects that straddle the line between signifier and functional structure, resembling both art installation and furniture. Each of Porky’s nests have so far mostly taken one of two basic forms: bird’s nests and animals. The bird’s nests are best exemplified by his “weaver’s nests,” which “copy the genius of the weaverbirds. The result is a human nest to be used outside, hung in a tree, or inside.” Each weaver’s nest can accommodate one to four people and is made by hand using traditional weaving techniques and organic materials, resulting in a structure of exaggerated proportion but unquestionable authenticity. The animals, some of which appeared at Design Miami this month, comprise his most recent series, Monstera Deliciosa and Otium and Acedia; the latter series represented South Africa in London. These are cartoonlike animals—mostly marine predators, such as killer whales, anglerfish, piranhas, and crocodiles—with enormous mouths that gape widely enough for a person to sit in.

The nests, despite their whimsicality and exaggerated forms, are not strictly designed for children. Rather, their child-friendly characteristics were originally determined by the limitations of Porky’s drawing abilities, which yielded a style that he found “too comical and almost childish” but eventually embraced. He describes his work as “quite rounded and spherical. It could be regarded as naive or unrefined. But it is dreamlike.” Scale is also important: “The beasts are all quite large, and this changes the ratio of your size to the object.” Among his animals adults tend to feel small, says Porky, as they did with their “first big teddy bear.” The result is that adult viewers feel like children, and children feel invited to behave like children, and climb on and play inside the animals.

Porky believes it is important to introduce children to the natural world, for their sake as well as the planet’s. He spent his childhood in South Africa, surrounded by animals of all sizes and descriptions, and he laments that most children don’t have access to that kind of experience, saying, “I don’t think the average child has much interaction with animals. Maybe a dog or cat or hamster, but not much bigger than themselves, where they feel a little scared.” His recent nests introduce children to animals they are unlikely to encounter in the wild, and though they are unrealistic, they offer an extremely heightened degree of interaction: The designer was able to approach dangerous animals as a child, but through his work children can now sit in the mouths of predators while enjoying safety and comfort.

Utopia was first and foremost a political tract, and through his nests Porky Hefer expresses an urgent political message. After reading a recent news article in the Guardian reporting that experts warn of a loss of two-thirds of wild animals by 2020, he felt confirmed in his view that “we need to somehow get kids to fall in love with animals.” Today’s children are set to take on the unenviable responsibility of compensating for previous generations’ failures in tending to the biosphere’s well-being, and any method of preparing them for that responsibility should be explored. For this reason it’s important that each of Porky’s animals is handmade and unique, providing children with a way to “feel for something they don’t know” through each object’s personality. Porky explains that Fiona, one of his orcas, is “smaller and rounder. Her skin is more perfect and flawless. She still has all her teeth. Lolita, on the other hand,” is an older orca. “Her skin is more marked, and her fins and tail bear the scars of a couple of encounters with other killer whales and the odd great white shark.”

The implicit messages of sustainability are put in tension by the construction and presentation of Porky’s animals, in keeping with Thomas More’s nuanced point of view. The word utopia comes from the Greek for nowhere, implying that a perfect world will always be out of reach, and Fiona, Lolita, and the other animals hang from cords, which produces a sensation of freedom, as if one is floating in water, but also evokes an image of a fish on a hook, captured and subjugated. Freedom cannot be total, and it comes at a price. Additionally, the pieces are made of leather, meaning that actual animals died for these representations of animals to be produced. Consequently, the designs simultaneously express idealism and darkness, doubtfulness. It’s possible that the best we can hope for is that Porky’s designs will inspire the next generation “not to fall into the sea of same. Not to work for corporations.” Whatever else he achieves with his work, his insistence on employing South African craftsmen to help him produce his objects with organic material, using traditional methods, supports local economies and cultures, contributing to a complementary political good.

Of course it’s unfair to expect a series of animal-shaped hanging chairs to save any local community, much less the entire world, but Porky never wanted to make chairs anyway. “I wanted them to have a life beyond being an apparatus for you to sit in. I see individuals with their own personalities and traits. Individuals who have a past and a future. I tried to get this to come across in the animals. I find chairs quite prescriptive. ‘Sit here. Sit like this and look at this.’ My beasts give you a lot more freedom.” With a Porky Hefer design, one does not sit on furniture; one coexists with Fiona or Lolita.

When I asked Porky if he had any additional thoughts on the interaction between his work and the child’s perspective, he said, “My whole business is probably a very childish idea. I feel blessed that I can make a life doing what I do.” What he does through his design, at the least, adds to the cumulative beauty in the world, and at the most, contributes to the world’s continued survival. Neither of these is merely childish.