004. COLLECTION

ICONIC PLAYTHINGS

Written by Lily Kane

During the middle of the last century designers and manufacturers began developing new materials and examining old materials in creative ways. The result was a collective rethinking, unprecedented in terms of speed and volume, of the built world. This rethinking didn’t apply solely to furniture and architecture, but carried over into objects meant to inspire children to create their own narratives and architectural spaces as well as to examine how objects are made and how they move. The value of these new toys was determined by the children who played with them, not the adults who created them: they were playthings.

Whether they make direct reference to them or not, all iconic modern playthings owe some debt to the “gifts” introduced in the late 1830s by Friedrich Froebel, a German pioneer in early-childhood development and education (and influence on Frank Lloyd Wright and Marcel Breuer). The gifts, which came in a simple wooden box, were a series of elegant, deceptively simple spheres, blocks, and connectors that encouraged interactive learning and creativity. Children received the objects one at a time so they could fully immerse themselves in what each object offered them at specific stages of development. Through playful observation and experimentation with these geometric forms, children learned about spatial relationships, movement, gravity, color, textural contrast, and more. The box of gifts allowed children to develop their innate ability to interact with the world around them and form a relationship with it.

The Tinkertoy, developed in 1914, can be considered the progenitor of the architectural toys of the midcentury. As the story goes, a stonemason named Charles Pajeau saw children playing with sticks and spent spools of thread. He created the Tinkertoy set—composed of colored sticks and a series of round, blond wood connectors—as an elevated take on these materials. Tinkertoy, like many iconic playthings, offers a blank slate so that children can build from their imagination—not a set of prescribed instructions to follow. There’s no “correct” object to build (though, given some inherent limits or suggestions presented by sticks and circular connectors, and because of the fair attraction’s popularity and novelty at the time, the Ferris wheel was a common display model).

Not all twentieth-century playthings were valuable for being building materials that children could manipulate in inventive ways. Some, such as the Slinky, gave children ways to reexamine the spaces around them. The accepted story is that an engineer named Richard James invented the Slinky in 1943 while trying to develop springs for stabilizing nautical equipment in choppy seas. Watching a box of springs fall off of a shelf, James found himself entranced by the way they moved, and even “walked.” He thought that others would be fascinated, too. After some trial and error, Slinky debuted at Gimbels department store in Philadelphia during the 1945 Christmas season. Over 200 million Slinkys have since sold to children and adults who have looked at staircases with fresh eyes after trying to urge their new toys into a replication of the effortless way the Slinky struts downstairs in advertisements.

Vintage Tinkertoys and Slinkys, despite being marketed to children, have become collectible among adults, meriting price guides and “classic” reeditions. (Toy collectors and longtime New Yorkers may remember Alphaville, a beautifully curated emporium of vintage toys at gallery prices on West Houston Street, across from Film Forum.) Adults have also borrowed iconic playthings from children for technological modeling, using Lego at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab, and Tinkertoy in robotics studies at Cornell University. And other iconic interactive playthings intended for children were claimed by design-savvy adults upon their introduction.

Imaginations of the young and old have been, and continue to be, sparked by the polymath Charles and Ray Eames and their studio through the furniture, films, instructional exhibitions, graphic elements, and toys they designed. In “Serious Fun,” an article for the Herman Miller magazine WHY, Alexandra Lange wrote that the Eameses’ goal was to “spark, but never limit, the young imagination.” In 1942, they used their “Kazam! machine” (the Eameses had a way of making everything sound like a toy) to experiment with coaxing plywood from linear sheets into graceful, molded curves. The resulting bent-plywood chairs, now global icons of midcentury modernism, set off several decades of some of the most inventive thinking in design. The ESU (“Eames storage unit”), adult-scale reconfigurable shelving designed for Herman Miller in the 1950s, came with instructions for converting the packaging into a playhouse once the ESU was removed, effecively producing as a byproduct an iconic architectural plaything.

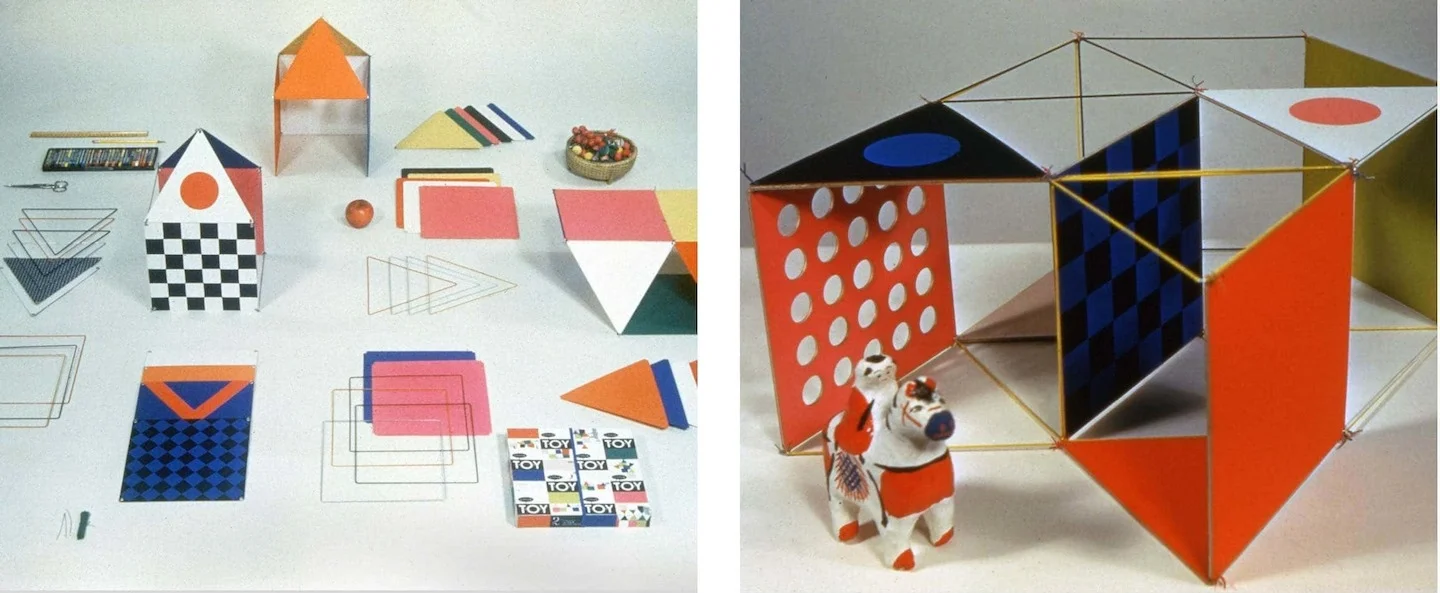

In perhaps a smoke-and-mirrors marketing ruse, or as an inside joke about folly, the Eames-designed Toy came on the market in 1951. The Little Toy, a “toy version of the Toy,” followed in 1952. The advertising copy pitched an object “for creating a light, bright expandable world large enough to play in and around.” Like Tinkertoy, the Toy is essentially just a set of geometric blocks and connectors, or “four 30 inch squares and four 30 inch triangles of heavy fire-resistant paper, 38 hardwood dowels, one pack of connection wires and instruction sheet.” A contemporary advertisement offering the Toy alongside a Ride-a-Boat as “the most wanted summer playthings in America” called the Eameses’ building set “the most imaginative plaything of the decade.” For children, suggested uses included “building a beach cabana, soft drink stand, sun shelter or boat.” And, for adults, “It’s a portable bathhouse!” Owing to the rarity—the Toy was produced only until 1959, and the Little Toy until 1961—the striking graphic design of the packaging, and the whimsy of the Eames office, this plaything that originally sold for $3.50 is now sold at auction to design collectors for hundreds of dollars.

Iconic midcentury playthings are not simply artifacts, frozen in time, but continue to influence today’s designers as well. Dutch designer Floris Hovers’s ArcheToys were presented at Dutch Design Week in 2007 and received immediate attention and reverence from adults. So much so, in fact, that they have already been acquired by the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam for its permanent collection. The name ArcheToy is derived from the word archetype. Hovers’s intention was to create forms that were “almost graphic impressions of the originals.” For instance, the shape of a tractor or a double-decker bus could be said to be imprinted in memory during childhood, from an experience seeing it on the street or in a storybook. Hovers’s ArcheToy hands the memory back as an elegant object meant to provoke nostalgia and narrative. He does the same thing with wooden and metal animals. The playthings’ apparent naïveté masks a sophistication and sensitivity that can be glimpsed in their expert craftsmanship.

Dezeen reported that objects for children were “one of the hot trends” at the 2016 Milan Furniture Fair. A roll call of designers creating smaller-scale furniture and interactive playthings, or reintroducing earlier works, was a who’s who of collectible contemporary-design all-stars: Eero Aarnio, Marcel Wanders, Nendo, Philippe Starck, Marc Newson. In the United States, the sculptural walnut blocks designed by Fort Makers are perhaps a twenty-first-century nod to the iconic midcentury block puzzles by Enzo Mari for Danese. They also strike the same balance between something a child would play with and something an adult might well put on a shelf to admire. If you think like a collector, now is a great moment to be among the first to own tomorrow’s iconic playthings.